“I am half agony, half hope.” These bittersweet words are perhaps the most memorable from Jane Austen’s last novel “Persuasion.” Unfortunately, the new Netflix adaptation of “Persuasion” is all agony and no hope.

As an Austen purist, this movie was outraging. It’s historically inaccurate and wildly different from Austen’s most mature and introspective novel. But, even for viewers who have never picked up a Jane Austen novel, it’s just as disappointing and forgettable. Netflix’s “Persuasion” is a bad, boring, cringe-worthy film. Contrary to Austen’s signature writing style, the film isn’t witty, clever, or inspiring, although like several of the film’s characters, it desperately tries to be.

In line with the current trend of modernizing period dramas, “Persuasion” unsuccessfully follows “Bridgerton’s” formula: aesthetic visuals, English accents, a pop-music-disguised-as-classical soundtrack, and political correctness designed to right the wrongs of early 19th century customs and culture. But unlike the substanceless, modern-day starting material of the Bridgerton books, Jane Austen’s works are literary masterpieces with universal themes and lessons that transcend time and do not need modernization. They deserve respect and dignity, and shouldn’t be passed off as cheap material for Hollywood to tout its politically correct agenda and attempt to redefine feminine virtue.

To set the stage, “Persuasion’s” leading lady Anne Elliot is in her late twenties and unmarried, making her a confirmed spinster and the subject of derision from her vain, unfeeling family. She was once in love with a charming young sailor, but he was without rank or fortune and thus an impractical choice. Anne was forced to give him up and wait for a more advantageous match, but she’s been pining for him for the last eight years. But her spendthrift father’s misfortune turned out to be Anne’s greatest blessing, as it forced her and her long lost lover Captain Frederick Wentworth back together.

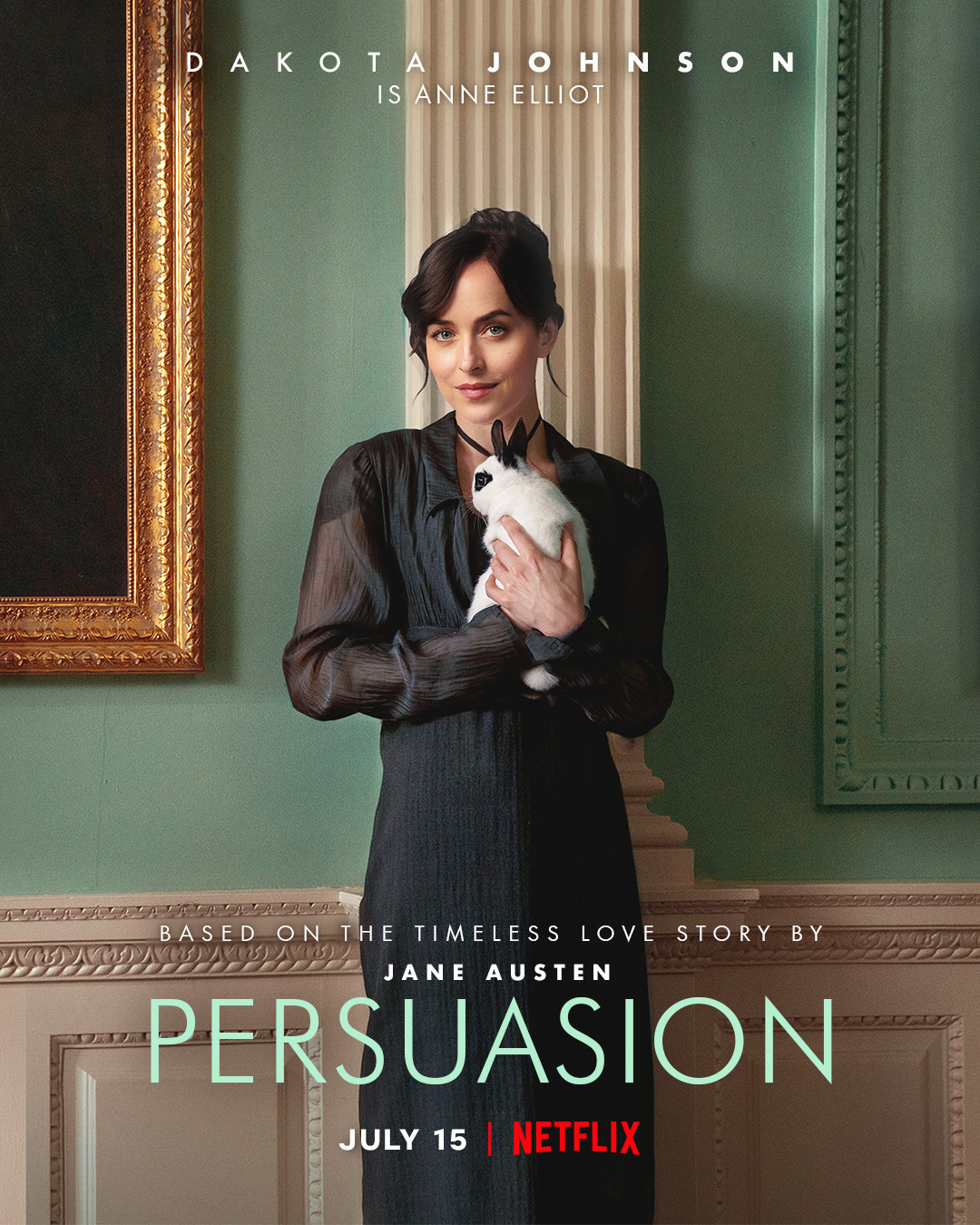

The most alarming part of this film was Dakota Johnson’s portrayal of Anne Elliot. Johnson’s Anne almost immediately breaks the fourth wall and speaks to the audience while making direct eye contact with the camera. It feels awkward and unnatural rather than intriguing the audience and giving a glimpse into Anne’s most introspective moments. She’s constantly winking, smirking, and rolling her eyes at the audience, while inserting modern day terms and phrases. “Wentworth and I are strangers. Worse than strangers,” she says. “ We’re exes.” Later she says of another suitor, “he’s a 10. I never trust a 10.”

This insertion of modernity negates the very reason our culture obsesses over period dramas: to escape our harsh reality of confused gender roles in love and marriage. This film scoffs at ridiculous men who spend all their money, are obsessed with their outward appearances, and “mansplain” the women around them. But, while Anne rejects her need for romance or Wentworth, she simultaneously blames him for not fighting for her affection and for running away from his feelings. The paradox that is Netflix’s Anne highlights the many contradictions of the modern-day feminist agenda.

Junior Alexandra Gess expressed disappointment with the film and said that Netflix’s adaptation is unsurprisingly a failure.

“I think Netflix’s adaptation of ‘Persuasion sucked the proverbial beauty, spirit, and life out of a masterful and beloved story in an effort to update a timeless classic,” she said. “It was a tactless, lackluster, and rather lousy attempt to make a Period piece more palatable to the postmodern 21st century.”

What is perhaps most concerning is that “Persuasion” follows in the footsteps of the 1999 “Mansfield Park” rendition by transforming the leading lady into someone completely unrecognizable from the original text. The quiet, mature, introspective, dignified, selfless Anne of Austen’s original work becomes a haughty, emotional, sarcastic, self-centered character in Netflix’s adaptation. Instead of lovingly serving those around her and coping with her grief in a private, dignified manner, Johnson’s Anne is a borderline alcoholic who pouts around and entertains herself through mocking her ridiculous family. Similarly, “Mansfield Park” transformed Austen’s quiet, humble heroine Fanny Price into a confident, boisterous, social-justice-warrior girlboss.

In an age begging for the acceptance and glorification of diversity, why do all period drama heroines have to be the same? Why are each of these characters, specifically written to reflect real women with different personality types, flaws, and dreams, morphed into sarcastic feminists who couldn’t care less about the virtues and privileges of femininity, family, and tradition?

Recent renditions of beloved Austen tales such as the 2020 version of “Emma” or the retelling of “Lady Susan” through the Amazon original series “Love and Friendship” show that intricate, meaningful text can be transposed for our modern-day society without cutting corners, injecting painfully obvious doses of 21st century life, or completely changing the main characters and the overall message of the story.

While ‘Persuasion’ is admittedly a difficult text to fully capture on film, as much of the tension between Anne and Wentworth is unspoken and relies heavily on past interactions unwritten by Austen, Netflix’s adaptation doesn’t even try to recreate the slow burn and suspense of their love story. Unlike the book, Anne and Wentworth appear to easily fall for other characters without any thought for their apparently deep connection, and although the audience can tell that they’ll eventually fall back in love, the ultimate resolution feels stunted and rushed. It’s questionable whether the Anne in the film truly loves Wentworth after telling her friend, “I would’ve been a far happier woman in keeping him than I have been in giving him up.”

This Anne is absorbed in her own happiness rather than loving and admiring the noble, loyal character of Wentworth. Anne’s unhappiness ultimately feels cheap, like nursing a pet wound out of boredom, rather than the true remorse and despair that Austen’s Anne so stringently portrays in the novel.

The only likable aspects of this film are, like Bridgerton, the costumes and the scenery. Anne’s sister Mary provides some comic relief from the monotony through her adoption of ridiculous modern-day quips and slogans. “The thing is, I’m an empath,” she knowingly explains to Anne. “What I’ve realized is I need to fall in love with myself first and then I can truly love those around me. ” Inserting modern-day humor and ideals into a period drama will of course warrant laughter, because it’s simply ridiculous. Thus, the only funny parts of “Persuasion” are cheaply thrown in by producers, and are a poor substitute for the subtle, witty social satire Jane Austen is remembered for.

Reception of “Persuasion” has largely been negative, with only a 32% positive Rotten Tomatoes score from professional film critics and reviews. We can only hope that Hollywood stops ruining timeless classics and producing content that will leave young women and girls with a distorted image of femininity.

So, if you think you can handle an awkward, confusing, infuriatingly predictable film, watch “Persuasion.” But hopefully, I’ve persuaded you not to.