Few phrases stick like “a good man is hard to find.”

Those words were probably uttered a thousand times before southern-gothic author Flannery O’Connor was born to Regina Cline and Edward Francis O’Connor in Savannah, Georgia in 1925 and wrote a short story by the same title 28 years later. They’ve probably been uttered at least a thousand times since. But were they ever drolled as Flannery drolled them?

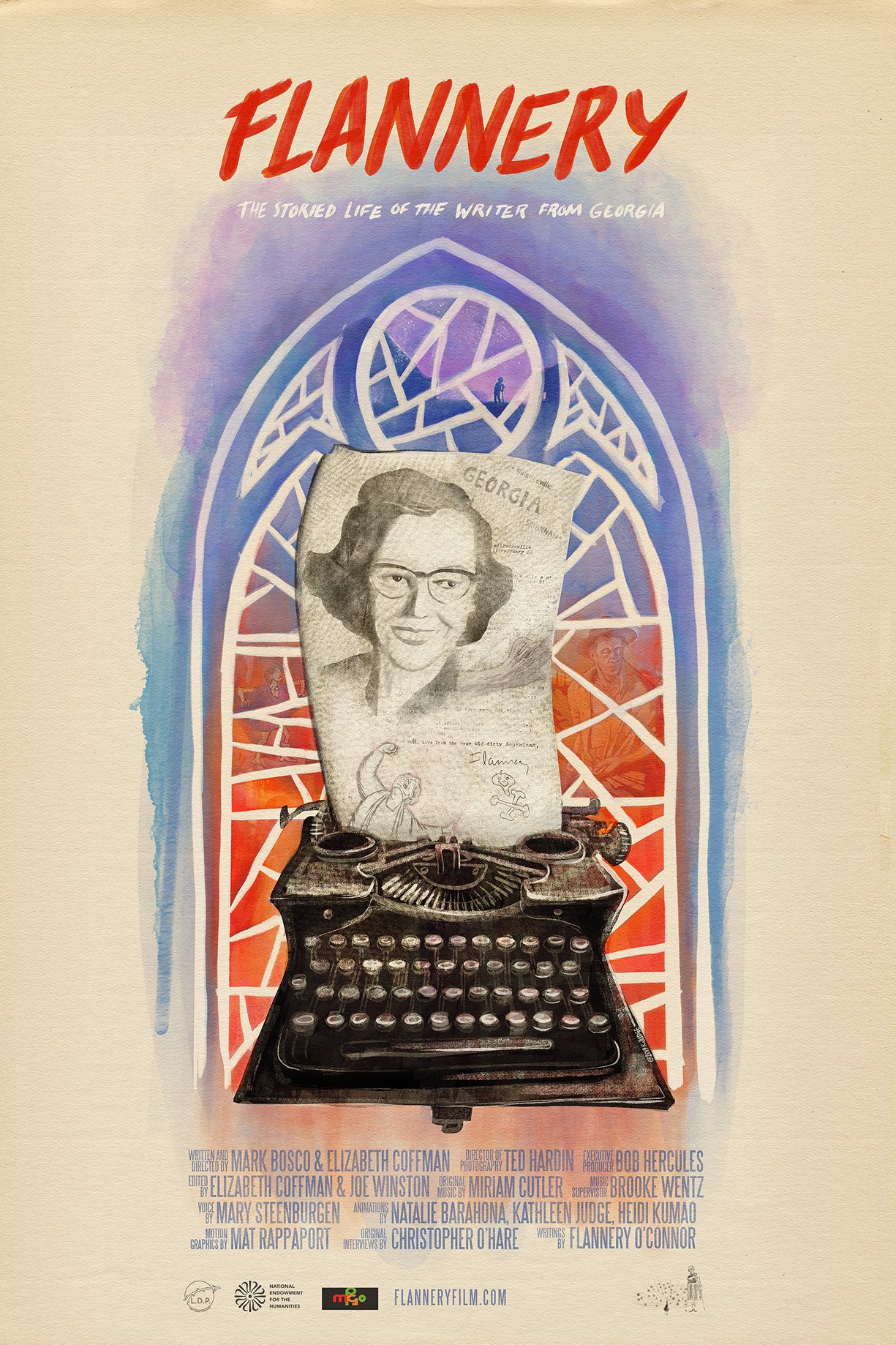

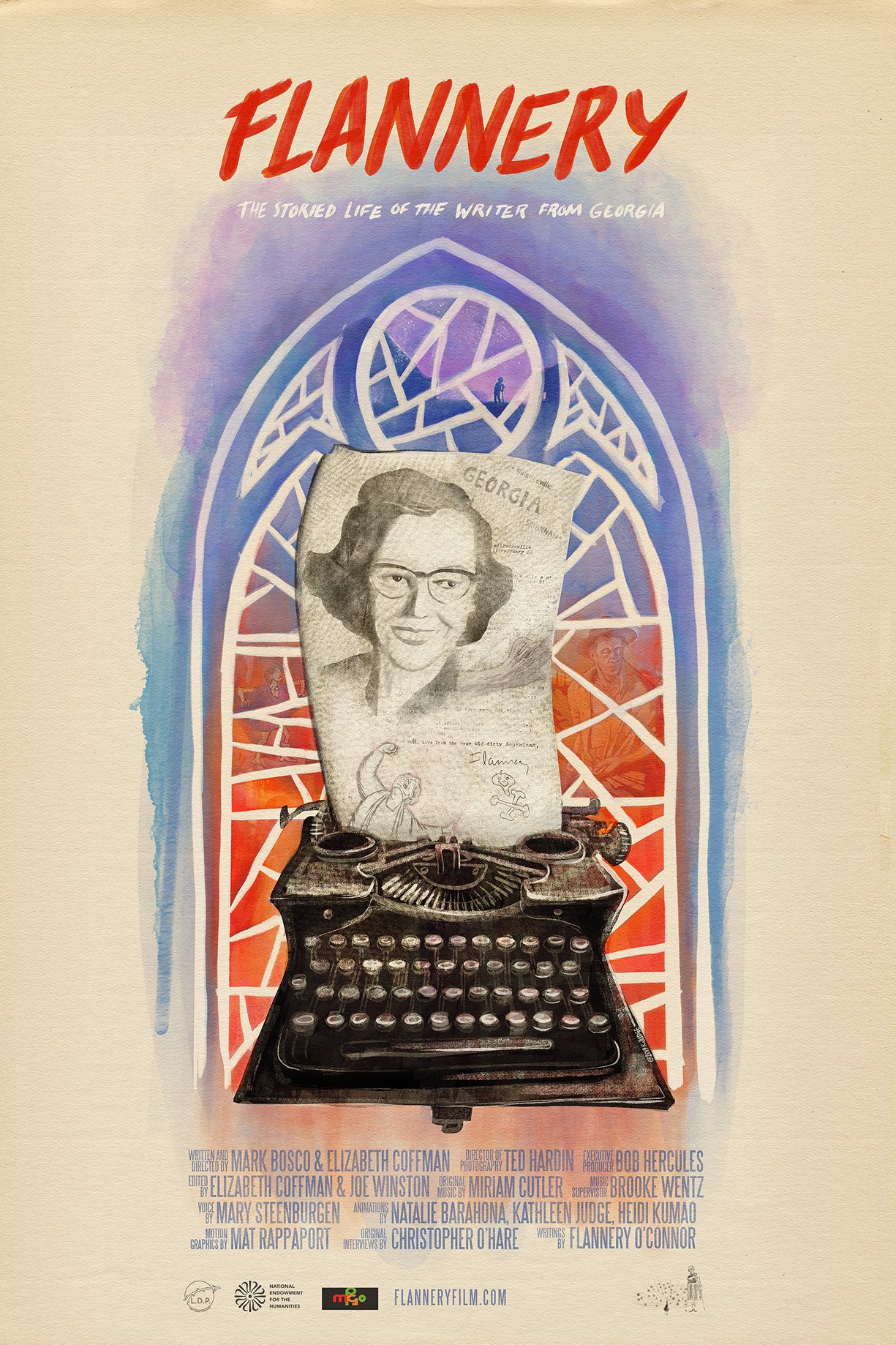

“Flannery: The Storied Life of the Writer from Georgia,” a new documentary by Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco S.J. and funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, tells the story of one of the South’s most legendary and least understood authors and her most popular short stories.

Released in October 2019 and screened on campus last Friday, the film wrestles with O’Connor and her paradoxes. “How can people go to church and commit murder?” the trailer asks. But more importantly, how did this southern, female author, who spent much of her life at home and died at 39 of lupus, learn to tell such grotesque stories of death and damnation, of blood and salvation, that have become staples in high-school literature classes across America?

To tell O’Connor’s story, Coffman and Bosco weave together historic photographs, footage from one of the writer’s only TV interviews, and interviews with some of the most influential people in O’Connor’s life — including Sally Fitzgerald, a close friend; Brad Gooch, her biographer; and Erik Langkjær, the only man who is recorded as having kissed her (“I’ve thought of it as a kiss of death,” he said of the moment). The documentary makers also incorporate original animations by Kathleen Judge to bring Flannery’s stories to life on screen. The effect is a documentary as colorful as O’Connor’s legendary peacock flock.

As an adult, Flannery remembered her younger self as a “pigeon-toed child with a receding chin and a you-leave-me-alone-or-I’ll-bite-you complex.” The film portrays this sharp sense of humor, from O’Connor’s high-school days as a satirical cartoonist to her oft-misunderstood written work later in life.

Other paradoxes are presented. How did one of the best American writers of the 20th century have practically every manuscript rejected (that is, until she met her publisher Robert Giroux)? O’Connor was a graduate of the famous Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and one of the best writers in her classes, much to the chagrin of her male colleagues. But until Giroux came along, editors wanted O’Connor to be nicer, to tell sweeter stories — in other words, to be more ladylike. O’Connor — either from knowledge of her own skill or sheer bull-headed stubbornness — would take back her manuscript and move along.

“I don’t deserve any credit for turning the other cheek as my tongue is always in it,” O’Connor once wrote in a letter to a friend.

Besides her wit, central to O’Connor’s identity was her Catholic faith. The documentary portrays, though perhaps misunderstands, the effects of this.

O’Connor’s stories often confuse the first-time reader by their subject matter (murderers, racists, heretics), which hardly seems religious. Catholicism does not equate with a theology of decency, for O’Connor. “A Temple of the Holy Ghost,” written 1954 and published in 1955, is one example the filmmakers use to demonstrate this. The short story deals with a precocious young Catholic girl who becomes obsessed with a hermaphrodite at the fair. During mass, the girl’s mind is occupied with the “freak,” rather than Christ, and until the consecration, she is thinking “ugly thoughts.”

Another of Flannery’s stories, “The Artificial Nigger,” has caused her to be banned from certain high schools for using the n-word, despite being one of the more pro racial equality writers of her time. The story examines Southern racism from the perspective of a white man and his grandson, visiting the city for the first time and, in the case of the grandson, seeing a black person for the first time.

Perhaps this edgy quality is just another paradox of Flannery, a girl who continually surprised her critics (especially her mother, who’s two primary dreams — that Flannery would marry and write about nicer things — were perpetually stymied). But Flannery’s singleness wasn’t what made her singular, though perhaps it’s the detail on which her observers have fixated the most. Like Hulga, her female lead in “Good Country People,” O’Connor defies expectations and is intentionally counter-cultural. But unlike Hulga, O’Connor never seems to be trying to prove herself. She just wants her wooden leg back. She just wants to write.

On closer inspection, O’Connor’s work is precisely what Christian writing must be.

O’Connor writes about strangers and outcasts and sinners, not simply because she herself was an outcast, as the filmmakers suggest, but because Christianity means living and breaking bread with precisely these “freaks.” Her work is pungent because it deliberately disregards the demands of decency. O’Connor’s stories portray a way of life that is as misunderstood as it is drenched in blood; it is life-and-death salvific.

O’Connor writes about death because it points to life. It’s shocking and it’s radical — but then again, so is grace.