Collegian | Carmel Kookogey

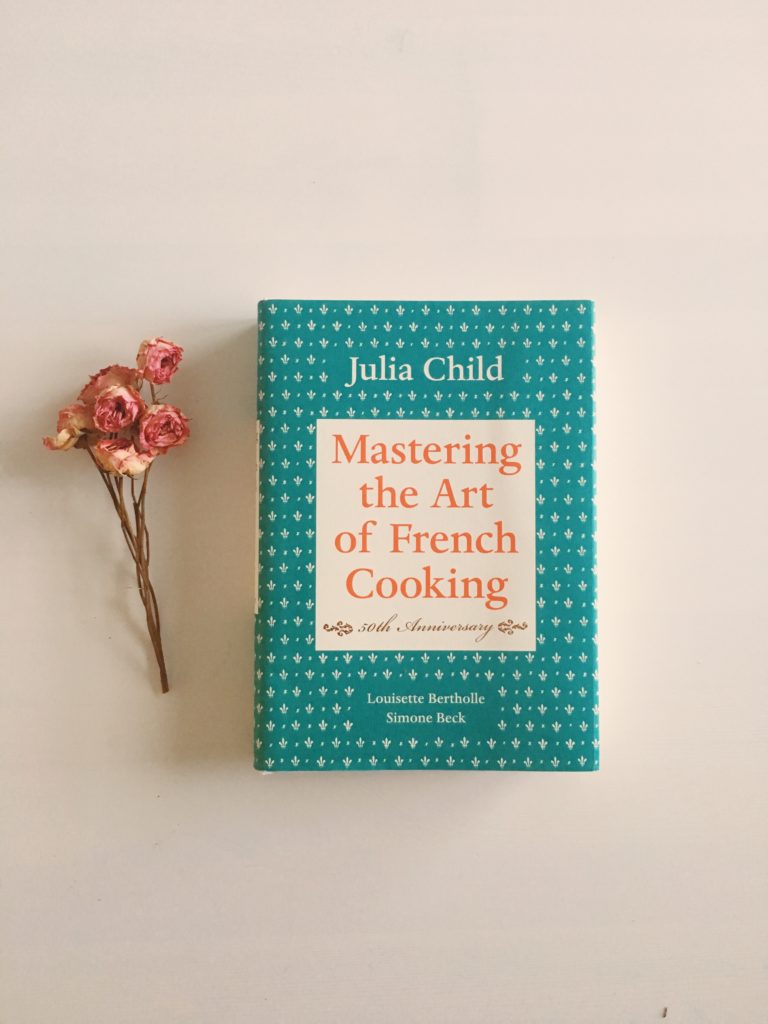

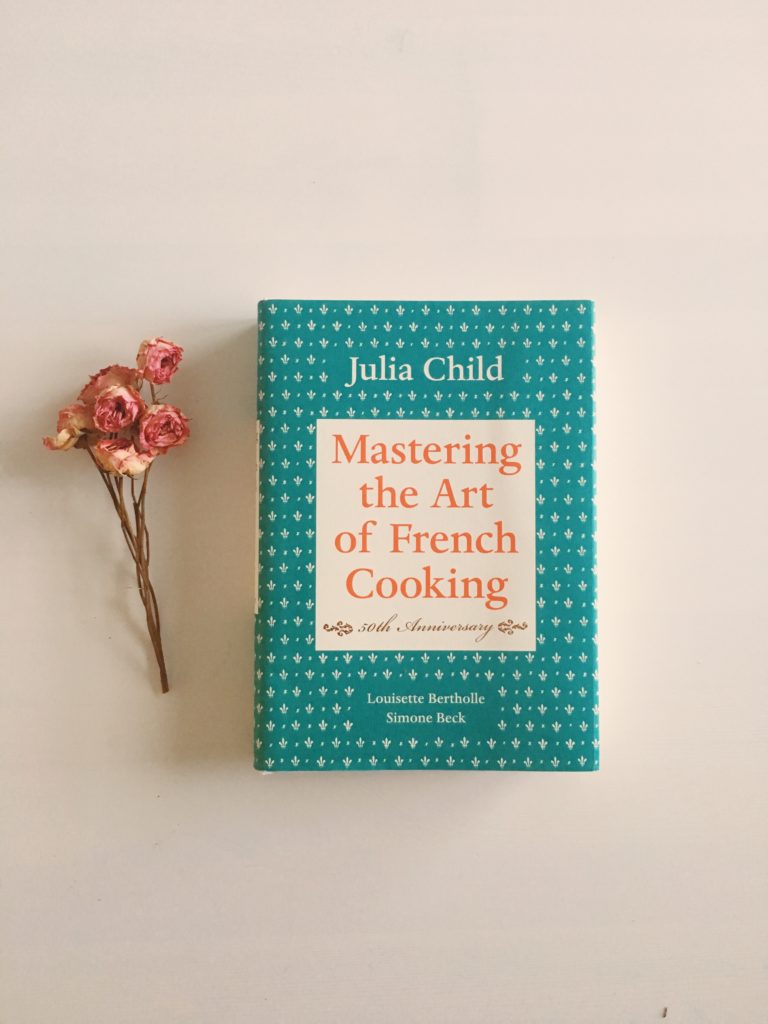

For Christmas this year, I asked for “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” by Julia Child, Louisette Bertholle, and Simone Beck, a cookbook published in 1961. I couldn’t wait to crack that famous teal-and-white cover and try my hand at a sauce chantilly or a coq au vin.

As I pulled back the box-lid on Christmas morning and started ooh-ing and ahh-ing as I thumbed through the pages, my dad asked, “Is that really the one you wanted?”

My parents were surprised that I would ask for Julia Child. Child was that French-cooking American woman from their childhood, the one they watched through the screen of old box television, who issued firm directives about the importance of courage in the kitchen in her distinct, uppity voice, and named a family of raw chickens before cooking them.

She was stuffy and weird when compared with the Gwyneth Paltrows, the Ina Gartens, and the Bobby Flays of modern food. On her television show The French Chef (1963-73), Child was known to throw out her own food if it did not turn out as desired, or cast the food as characters in a story she told while cooking, as in “Goldilocks and the Three Brioches.”

And it’s true, Child was no classy French woman in her demeanor, as anyone can tell you who has watched Meryl Streep play Child, squeaking with Stanley Tucci about butter in the 2009 film “Julie & Julia.” She was an American who once asserted “every woman should have a blowtorch” and who wanted to bring the French cuisine she loved to eat to the women back at home.

In a way, Child’s approach to cooking was the liberal-arts approach to education: You have to prove you’ve learned the rules before you can go and break them with artistic license. And she is strict about getting the rules right.

Child’s cookbook has become a classic and earned its recognition. She brought the ethos of French cooking to the American housewife, with traditional French emphasis on perfecting basics, and finding not only the best but also the simplest ingredients.

“How can a nation be called great if its bread tastes like Kleenex?” Child once said. She loved creating rich yet simple food.

In mastering the art of French cooking herself, Child evokes in her readers a desire to do the same: to take something as basic as a chicken and make it mouthwatering in its own right, without needing to add exotic spices or shocking flavor combinations — not because rich flavors are the mark of a poor cook, but because understatement is the mark of French cooking. It’s an art that has become especially relevant in modern “more is more” culture, suggesting instead a spirit of restraint (except, of course, with butter).

I love that modern technology has enabled me to attempt mastery of Indian, Asian, and Mediterranean cuisine, all in my own kitchen. I love that we have the option of filling our mouths with spices and flavors that earlier generations of Americans could not easily access. I love cooking with robust flavors. But there is something to be said for Child’s emphasis on the basics.

“You don’t have to cook fancy or complicated masterpieces — just good food from fresh ingredients,” Child wrote.

Most of her recipes use only a handful of ingredients. Her instructions are ruthlessly detailed. The result, a beautiful poulet rôti à la Normande, cooked in oodles of butter, that is as delicious as it is simple.