Southern Michigan is in one of two narrow latitudinal bands where any remnants of the Tiangong-1 spacecraft might land when they re-enter the atmosphere, although most of it is expected to burn up upon re-entry.

The spacecraft is now projected to fall sometime between March 30 and April 8, according to the European Space Agency.

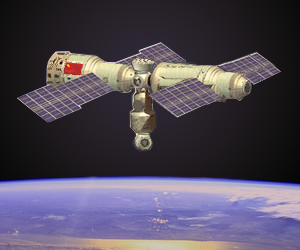

The Tiangong-1, an 8.5-ton Chinese space station containing corrosive fuels, was launched in 2011 and finished its mission in 2016. Soon after that, scientists lost control of the station and initially expected it to fall from the sky in late 2017, according to the Chinese space agency.

The general concern about the presence of corrosive fuel remaining at the time when any remaining chunks land on the ground is low, according to Assistant Professor of Physics Timothy Dolch.

“The fact that there’s still some fuel in the tanks may make the re-entry safer because once those explode, the station will be obliterated into smaller pieces,”Assistant Professor of Physics Timothy Dolch said. “The more small pieces you have, the easier it is for those small pieces to burn up.”

No re-entry can be 100 percent controlled, but Dolch said the Tiangong-1’s re-entry is considered less planned than usual. The spacecraft is incapable of velocity boosts to increase its orbiting speed.

The Tiangong-1’s low orbit is close enough to Earth’s outer atmosphere that the drag from the atmosphere gradually weakens the spacecraft’s orbit.

After years in low-earth orbit, the spacecraft must eventually spiral down and crash.

Because of this reality, things that are in low-earth orbit receive velocity boosts and occasional corrections to their orbits, which is why the space station had a fuel tank on it.

The Tiangong-1’s ability to make these corrections, however, malfunctioned at some point, according to reports from the Chinese space agency.

Although this malfunction makes the Tiangong-1’s re-entry less controlled, Dolch said it should not be too dangerous.

“It’s nothing to get an insurance policy over,” he said.

Dolch said the Tiangong-1 could re-enter any time over the next few months, but the exact location of re-entry depends upon where it is in its orbit.

There have been many other examples of such events with improbable, but severe potential risks, Dolch said. In 1997, the Cassini–Huygens mission was launched, and it ultimately burned up in Saturn’s atmosphere in September 2017 in an event referred to as “the grand finale.”

Dolch said the Cassini-Huygens launch was considered controversial because of a small chance that radioactive material could rain down over Florida.

“There was something like a 99.9 percent chance it wouldn’t happen,” Dolch said. “I think the Cassini example was far more risky than this. So that’s how I look at it.”

Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at Harvard University, told The Australian the way to eliminate such risks is controlled re-entry.

McDowell said about 40 percent of rocket stages in space now can restart their own engines and alter their orbits. Most satellites bigger than about five tons come with motors that allows their controllers to aim them when the disposing of them, he said.

Nobody has ever been hurt by re-entering debris, according to the Aerospace Corporation.