There are a few conversations that music junkies would kill to overhear, and here’s one of them: Dylan and Cohen on a California road trip, reminiscing about the golden days of ’60s rock ’n’ roll.

Several weeks before his death in 2016, Leonard Cohen replayed his memory of the conversation for the New Yorker.

In Cohen’s retelling, Bob Dylan’s classic 1966 hit “Just Like a Woman” came on the radio. After humming a few bars, Dylan turned to Cohen and told him that a famous songwriter had recently remarked to him, “Okay, Bob, you’re Number One, but I’m Number Two.”

In typical Dylan fashion, he used the opportunity to give his road trip partner a wry compliment.

“As far as I’m concerned,” Dylan said. “Leonard, you’re Number One. I’m Number Zero.”

That’s probably the best assessment of the 1960s — a musical moment that a still-shocked-and-awed Jody Bottum outlined in his CCA talk Tuesday night, with some uncertainty about what it all meant: “It wasn’t Beethoven’s Ninth, but it was something.”

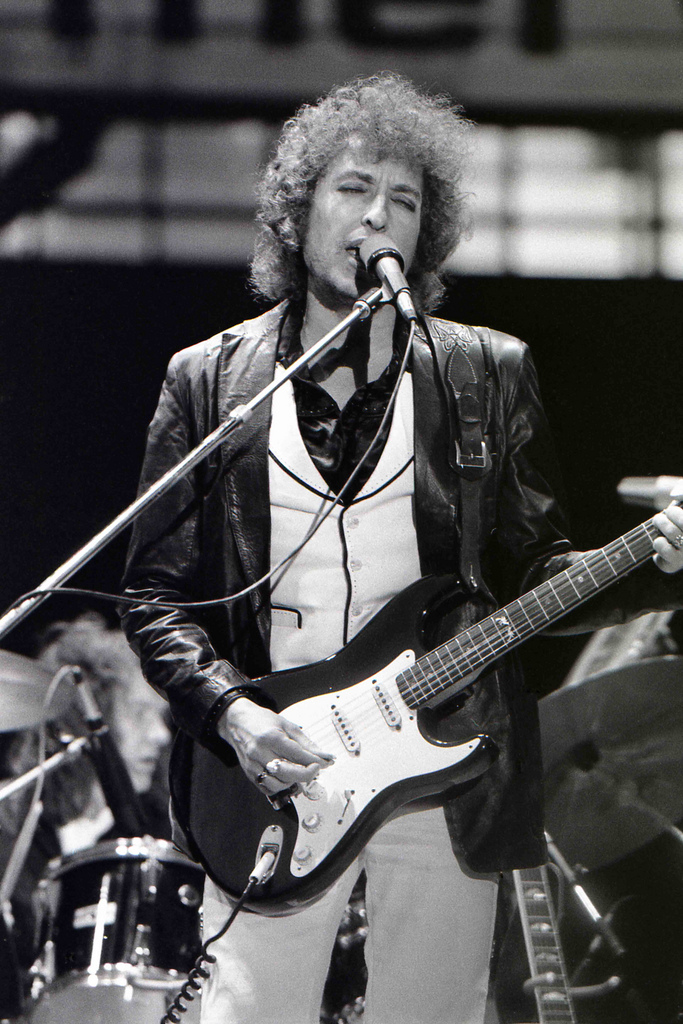

And it was just that: Something new, something unprecedented and hard to define. In the ’60s music movement, technology, politics, and cheap speakers exploded into a psychedelic array of earworms, smash hits, and headtrips. It was a musical free-for-all, and amidst the confusion, songwriters like Cohen could still score hits by telling love stories with old guitars. But only Bob Dylan’s genius transcended and transformed pop music.

Dylan came onto the scene at the right time. In the ’60s, audiences and artists made a mutual (and perhaps unspoken) pact that pop music was important and needed to be treated with reverence. “Like A Rolling Stone” became an anthem for the disillusioned. “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” gave voice to the downtrodden. Even the 11-minute dirge “Desolation Row” was taken seriously, and eventually deemed Nobel Prize-worthy — despite Weekly Standard columnist Andy Ferguson’s vehement protestations.

Cohen stumbled into pop music shortly after Dylan’s nationwide success. Already established as a failed Beat poet (check out his aptly-titled novel “Beautiful Losers”), Cohen turned to songwriting because fiction was not paying the bills. Like Dylan, he was a Jew who drew on a deep reserve of Biblical and cultural history for his lyrics. But Cohen never waded into Dylan’s free ’n’ easy waters; he stayed fixed on the shore, looking out at the hippies’ so-called “Age of Aquarius” with a lover’s gaze.

Cohen’s seminal hit, “Hallelujah” — and everybody’s favorite Jeff Buckley cover — did not come out until long after the ’60s had spun into the excess of the ’80s, but it is essentially a child of the same era that produced his early break-out hits “Suzanne” and “So Long, Marianne.” Cohen spent five years writing “Hallelujah,” and a whole lifetime living its broken victory march.

Cohen and Dylan combined their observations of time’s passage into eternity in a way that set them apart from their peers. The ’60s was a diverse and ephemeral time, wrapped up in its own contemporaneity. It put the acid-drenched folk band The Grateful Dead, the hard rocker Jimi Hendrix, and Bob Dylan’s most-attractive cover act Joan Baez on the same stage, but none of these acts (except maybe The Grateful Dead) escaped the era they helped define. Cohen and Dylan were acutely conscious of their place in the era — and that’s how they transcended it.

This is how these songwriters became voices that still speak for an entire people. Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which was originally conceived as a ballad about social unrest, still speaks for the deep human longing for respite from the world. Similarly, Cohen’s “So Long, Marianne” talks about love and loss in a way that still makes its listeners’ hearts ache.

But every work of artistic greatness resonates from within its own time. Cohen and Dylan’s lyrical music, relatable as it is for all ’60s sons and lovers, is self-consciously political as much of the message-driven rallying cries of the revolution-rabid decade. Both songwriters aced a lesson they purified later in their careers: Music is politically and culturally powerful, as long as you can convince people to believe it is.

Dylan isn’t afraid to ask in his music: “How does it feel?”