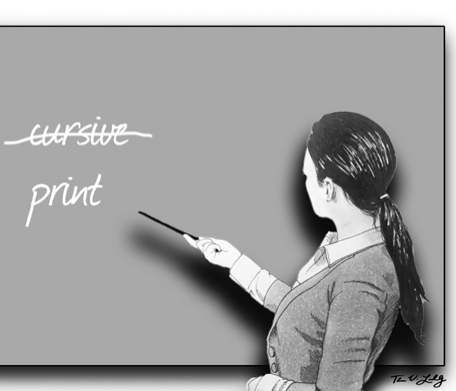

Forty-five states have adopted the Common Core State Standards in education, cutting cursive from school curricula. Because of the 21st century notion that students don’t need to learn cursive, they spend about 10 minutes per day practicing handwriting, a dramatic decrease from an average of 45 minutes per day in the 1960s and 1970s.

To many modern educators, a page bedecked with cursive words has as much practical value as a printing press. It’s a relic of a bygone era. They believe teachers should replace time spent on penmanship with time spent typing, scrolling, and discovering the wonders of the Internet.

Swapping handwriting for type may not be without consequences, however. Learning cursive teaches lessons essential to students, and studies show that writing by hand is good for the brain and productive for young students’ mental development.

Steve Graham, a professor of education at Vanderbilt University, is renowned for his research on handwriting. His work indicates that “from kindergarten through fourth grade, kids think and write at the same time.” He also suggests that cursive can improve left-right brain coordination.

In one 2012 study, psychologists used fMRIs to monitor the brain activity of two groups of preschoolers learning the alphabet: one by typing, the other by printing. The fMRI revealed that a writing and typing engaged different parts of the brain, and that writing by hand imprints more deeply on the brain than typing does. The students who learned by writing were better able to distinguish characters and the corresponding sounds when tested. There’s something in the physical act of forming the letters that commits them to memory.

Latin curriculum author Cheryl Lowe writes that, in a time when teachers are constantly seeking opportunities for hands-on learning, they should be thrilled to have their students practice handwriting in class. Handwriting is the ultimate hands-on learning opportunity, says Lowe, as it links mind and body together in an intellectual pursuit, “what education is supposed to be about.”

But the lessons that learning cursive teaches are more valuable than the ability to write cursive. Lowe believes that learning to write well teaches lessons beyond itself.

“Penmanship teaches the beginning student the basic skills of accuracy, correct spelling, and the patience and persistence required to do quality work,” Lowe says.

All of these qualities are beneficial, even necessary, to become a good student, and they only help in life after school.

Mastering the subtle distinctions of handwriting at an early age teaches students that detail matters and that there is value in doing things correctly, maybe partly because it takes time. And maybe American test scores wouldn’t be plummeting to record lows if curricula placed value on getting things just right, rather than just somewhere in the ballpark.

The philosophy that does away with cursive does so in the name of king efficiency. But crowning efficiency validates the question nearly every student asks at some time in his academic career that irritates teachers to no end: “Why do I have to learn this? I’m never going to use it. It won’t help me get a job.”

These are the wrong questions, the wrong assumptions. Learning isn’t about efficiency. Learning is about peering into the world outside of yourself, knowing that much is to be discovered there if only you look long enough. And more often than not, learning is slow.

Hillsdale College Professor of History Mark Kalthoff wrote an article for “The Imaginative Conservative” that lays out what it means to truly learn. He says that learning begins in stillness, “the starting requirement for the exercise of contemplation.” Contemplation implies a careful sifting of ideas, something that takes time.

Inherent in learning cursive is the idea that faster is not always better. Cursive teaches habits of deliberateness and care which are foundational to learning well. It may not seem most efficient, but when educators are tempted to make speed their first priority, they should remember the Latin phrase written on my suitemate’s door. Festina lente. It means “to make haste slowly.”