Suzanne Wolfe’s Facebook page | Courtesy

A sputtering flame casts shadows over the scholar’s face as he pores over the Scriptures, his bent body forming the perfect image of a studious disciple. It’s late, and the words blur on the page.

Saint Augustine snuffs out the candle and falls into his concubine’s arms.

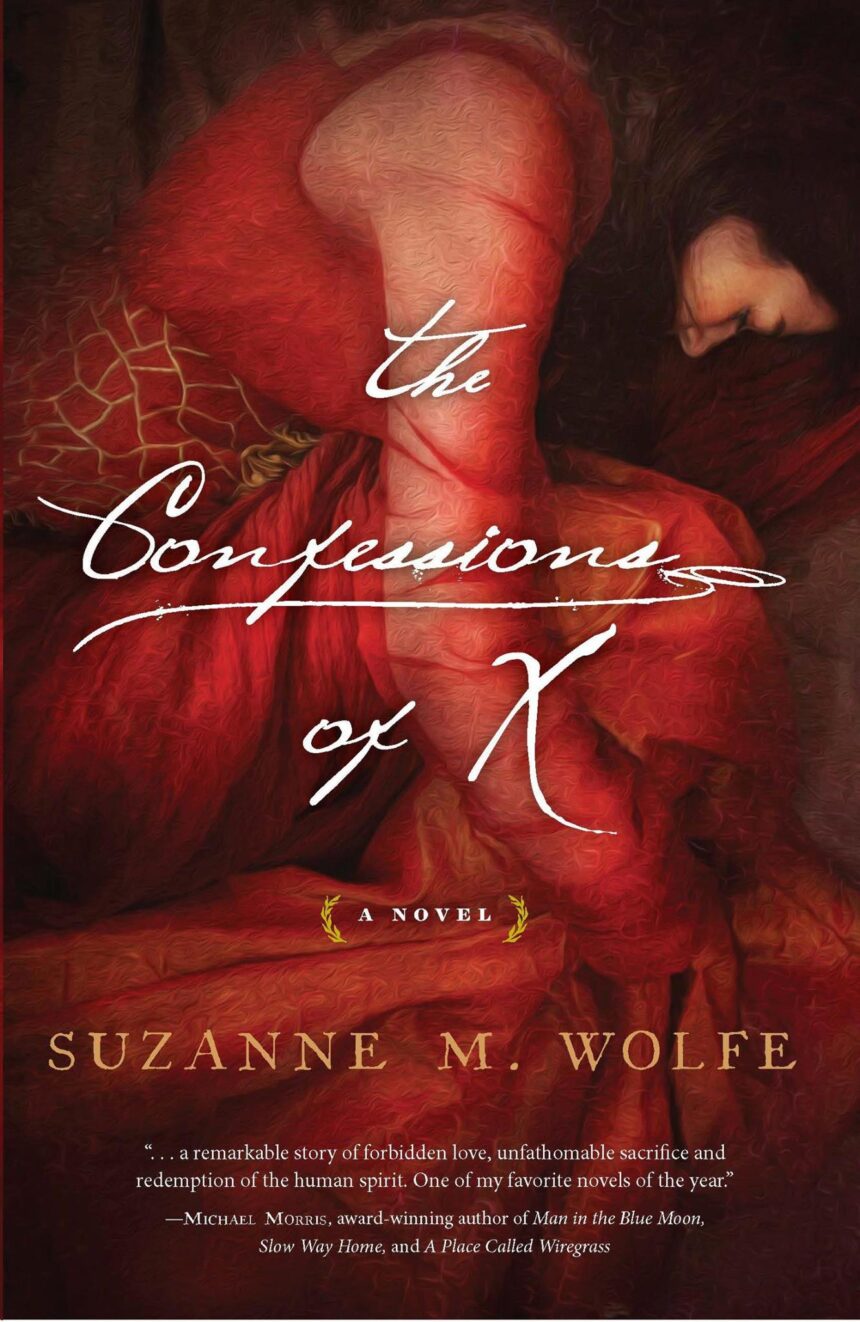

In “The Confessions of X,” Suzanne M. Wolfe reimagines Augustine’s secret love life, following the formation of the influential theologian’s life and thought through the eyes of his mysterious lover. But this novel is no expose. Wolfe, the co-founder of “Image,” a literary journal devoted to religion’s relationship with the arts, creates a vision of a virtuous woman whose life embodied the doctrines of love, faith, and sacrifice that inspired Augustine’s “Confessions.”

When Wolfe first read “Confessions,” she was struck by a glimpse into Augustine’s private life with a woman he refers to only as “Una,” or “the one.” After devoting his life to theology, the budding scholar reluctantly broke off this relationship in order to further his career. Augustine never remarried, and he remembered their relationship years later:

“This blow crushed my heart to bleeding because I loved her dearly.”

Intrigued by this doomed love affair, Wolfe soon learned that Augustine’s devotion to his concubine was no scandal. In fact, such “common-law marriages” were normal in a time when marriage between social classes was discouraged. From this story of star-crossed lovers, “The Confessions of X” was born.

Wolfe calls this anonymous woman “X,” the daughter of a mosaic artist and a powerful artisan of images in her own right. X tells her story with warmth and wisdom: her childhood with her vagrant father taught her to see life as the “art of broken things.” Her whirlwind courtship with Augustine, though it could never end in marriage, infused her life with love. And her life with him, though it ended in loneliness, produced her greatest work of art: her son Adeodatus.

X tells Augustine “I think best in pictures,” and the novel’s luminescent prose brings ancient Carthage to life in vibrant color. But Wolfe’s narrator is more than a roving pair of eyes watching her lover’s growth as orator, teacher, and theologian; the pictures she paints with her words lead readers — and Augustine himself — to profound insights.

The young philosopher’s debate over good and evil is uprooted when Wolfe paints God’s will as a flower. Rooted in darkness, it grows toward the light.

And when X sees beauty as “the yeast in the bread” of life, the Manichean debate between reality and the spirit goes up in smoke.

Though X’s storytelling is visionary, her life is a testimony to something both below and beyond abstract pictures of love. The force of the novel stems from X’s feminine voice; for the mother of Augustine’s son, love must be incarnational, rooted in the physical bonds that tie man to wife and mother to son.

Wolfe explores the question of women’s roles without molding her narrator to the well-intentioned but narrow stereotype of the “strong female character.” Wolfe’s heroine is neither a crusading feminist nor a stand-in for an ambitious male hero.

Instead, X is portrayed as a woman of her time, respecting her husband and conforming to social norms regarding marriage between classes. But Wolfe also paints a Christian idea of marriage in the ill-fated but loyal relationship between concubine and future church father.

Other female relationships in the novel reinforce this incarnational view of love. In “Confessions,” Augustine credits his Christian conversion to his mother, Monica. Wolfe’s Monica is a firm but devoted mother who accepts the vulnerable X into her family in an act of love that sows the seed of faith for her son.

Though her relationship with Augustine was controversial, her justification for her love and inevitable loss is convincing.Throughout the novel, X uses metaphors of birth to illustrate a woman’s calling to nurture men and push them into the world. The strength of all women — not only ill-fated concubines— lies in their sacrifice as they let their loved ones go.

In “The Confessions of X,” readers will discover their debt to women like X, lovers and mothers who supported and inspired great men like Saint Augustine by serving as images of sacrificial love.