On Nov. 2, 1930, a young man snapped the last color photo of an Ethiopian prince being crowned emperor. Excitement rushed up his spine as he watched the ceremonies, he described in his memoir. He didn’t know Emperor Haile Selassie I would be killed years later by a communist coup, ending the 3,000-year monarchy.

The photo was later published by National Geographic in 1931, with a small subscript underneath: “photographer: W. Robert Moore.”

Moore graduated from Hillsdale in 1921—and in a letter to the Hillsdale Alumni magazine in 1932, he wrote, “when Hillsdale gave me my diploma in 1921 and told me that the whole world was before me, I took it quite literally.”

This simple camera snap began Hillsdale’s nearly 100-year relationship with Ethiopia. It was a deep relationship marked by the dedication of a selfless ambassador, Hillsdale alumnus Ross Adair, ’28, (nearly a third of the Ethopian senate escaped to Fort Wayne, Indiana, because of Adair). It was a story of the unconventional hospitality of Hillsdale College professor and nationally renowned intellectual, Russell Kirk.

This story was mostly forgotten — until now, thanks to the work of a student filmmaker.

On Jan. 18, six students showed up to “Video Storytelling,” a new class taught by documentary filmmaker and journalism instructor Buddy Moorehouse. The goal of the course was simple: “You are here to tell stories about Hillsdale.” Hillsdale alumni. Hillsdale students. Hillsdale history.

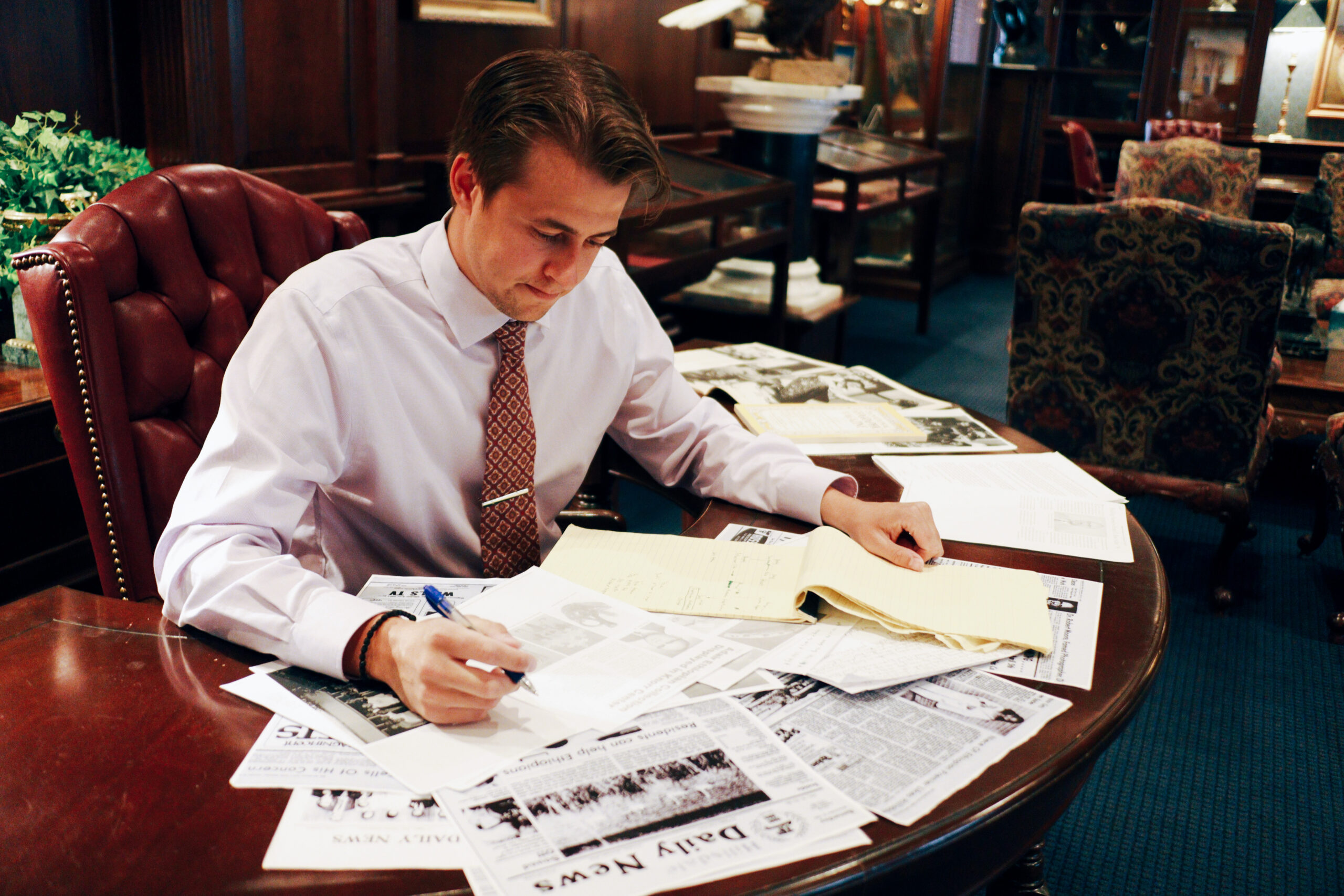

Most of these projects are capped at five minutes, and the final project for the class is a 30 minute documentary on the 1955 Hillsdale College football team and the Tangerine Bowl. But senior Stefan Kleinhenz will finish the course with an hour-long film, “Royal Refuge,” which details the story of how Hillsdale College and its alumni and faculty became a safe haven for Ethiopian refugees during the fall of the Ethiopian monarchy.

“The monasteries in the Middle Ages were kept alive with the manuscripts and, in some sense, that’s what colleges should be doing. They should be keeping alive the past through their manuscripts and discussions and talks — and now, new techniques of filming,” said Annette Kirk, wife of the late Russell Kirk. “Stefan is continuing that work of keeping culture alive.”

The documentary will premiere on April 27 in Plaster Auditorium at 6 p.m. Refreshments will be provided. This is the first film produced by “SteFilms,” Kleinhenz’s small documentary company which he started after taking this class.

The hour-long film started out as Moorehouse’s second assignment to make a five-minute documentary on any event in Hillsdale College history.

Kleinhenz said his project needed to be something unconventional and unique. Ronald Reagan’s Hillsdale visit or Central Hall burning down wouldn’t suffice. Good storytellers tell stories never told before, he added, a serious look in his eyes.

One conversation with his adviser, professor and chair of rhetoric and public address Kristen Kiledal, sparked his project.

“I was walking her to her car because she had to go but I kept wanting more ideas, and she turned down the stairwell, and said, ‘Wait, there were African nobility here in the ’70s,’” Kleinhenz said. “That’s all she remembered. And I said, ‘That’s it. That’s the story.”

For four full days, Kleinhenz raided the internet, books, and library archives. Initially, he found nothing. In a final attempt to find something on ‘Ethiopian Royalty,’ Kleinhenz emailed Robert Blackstock, who served the college as both the provost and a professor for more than 40 years. Maybe he would remember the African nobility who studied at Hillsdale, Stefan thought.

Blackstock gave him a name: Mistella Mekonnen.

“It was the most beautiful email I’d ever gotten because it sent us on a way,” Kleinhenz said, referring to Kiledal, who had become his research assistant. “With that name, everything came through because it had something I could search.”

The name unlocked more details. Not only had Mistella Mekonnen, who herself was Ethiopian royalty, come to Hillsdale as a student in 1974, but came on the recommendation of Ross Adair — a Hillsdale alumnus and the United States ambassador to Ethiopia at the time.

Adair and his wife Marian ’30 became a friend to the Ethiopians, said Kleinhenz, so much so that the royal family trusted his advice and sent Mistella to Hillsdale.

“We’re one of the first ones in the country that admitted everybody no matter what their gender or their nationality or their race — everybody was welcome to Hillsdale College,” Moorehouse said. “That was true in the 1800s and that’s true in the ’70s when Mistella came here.”

Kleinhenz uncovered the whole story. While Mistella studied at Hillsdale, communists imprisoned Emperor Salassie as a part of their coup. He was killed one year later. People began to protest against the oppressive regime, and Mistella’s sister was killed in one such protest. Shortly after, Russell Kirk, one of Mistella’s professors, welcomed the rest of the Mekonnen siblings to his home in Hillsdale as refugees.

“When he called me up from Hillsdale and said that a young student in his class had approached him and asked him if we would consider taking her sister and brother for a while because they needed to leave there due to the war that was raging at the time, my immediate reaction to that was, ‘Where is Ethiopia?’ said Kirk.

The pieces all started to come together for Kleinhenz, and as he found more and more information, the five-minute film turned into 10 minutes. Ten minutes became 30 minutes, and soon the assignment became Kleinhenz’s senior thesis project. He worked nearly 40 hours a week on the film for more than 10 weeks.

He dug through old archives, interviews, and photos, both online and in libraries. Within weeks, he had to become an expert on iMovie, the video software. He also handled nine different interviewees on nine different schedules. He found Mistella. He zoomed with Steven Adair, Ross’s son. He interviewed Dan Quayle, Vice President of the United States under George H. W. Bush, and a colleague of Ross Adair during his time in office.

Finding them was the hardest part, Kleinhenz said.

“When I call Steven Adair, Ross’ son, on a Saturday afternoon, I’m hoping he’s not bothered by the fact that I have his phone number,” Kleinhenz said. “I’m cold calling him hoping that I can give him a good enough pitch that he’s not concerned about who the heck I am.”

“It’s not as easy as ‘Stefan, here’s a list of 10 people with their phone numbers and addresses,’’ added Moorehouse. “No, he had to track down all of these people, and I don’t think there’s a single person who turned him down for an interview.”

Slowly, these interviewees became friends, Kleinhenz said. His heart connected to theirs, and their stories became his. Some interviews unearthed special connections. Stefan is Greek Orthodox, and Mistella is Ethiopian Orthodox.

“As a filmmaker, to make a connection like that with someone who you’re doing a story on, it makes it that much deeper and that much more personal. We can trust each other,” he said.

A good documentary is one which tells a story in both a compelling and cohesive way, explained Moorehouse. The B-roll — or the supplemental shots throughout the film — needs to engage the audience, as must the narration. Moorehouse taught Kleinhenz how to narrow his information to tell a succinct story.

While Moorehouse worked with Kleinhenz on the technical video work, Kiledal molded his story. The two worked together to collect clues and form the story. Kiledal remembered the front of a LIFE Magazine cover with Ethiopian Royalty on it. Though they still haven’t found that magazine, the two found another LIFE issue, which revealed that Adair brought several members of the Ethiopian senate to Indiana for refuge.

“His joy motivated me,” Kiledal said. “He had great training already in journalism from Mr. Miller and Mrs. Servold. He had broadcasting experience from One America News, and Stefan had the documentary teacher. He just needed a research mentor and someone who would care about the project with him.”

Steve Adair, Ross’ son, said his parents would be very thankful for Kleinhenz’s project.

“I hope he gets an A-plus.”

This documentary was more than a one-time project, said Kleinhenz. It’s the beginning of his new career. He’s dipped his feet in all sorts of journalism, from newspaper writing, to radio, to even television. He’s worked as a TV reporter in Washington, D.C. He’s won several radio awards throughout the state of Michigan and some national ones, including first place in a News Interview from the Intercollegiate Broadcast System.

But documentaries are now his calling, he says, smiling with confidence.

“This is what I was preparing for and I didn’t even know it,” Kleinhenz said. “Documentaries are real. They’re about humanity, and if you tell the right stories and you tell them well, it’s going to matter for a very long time.”