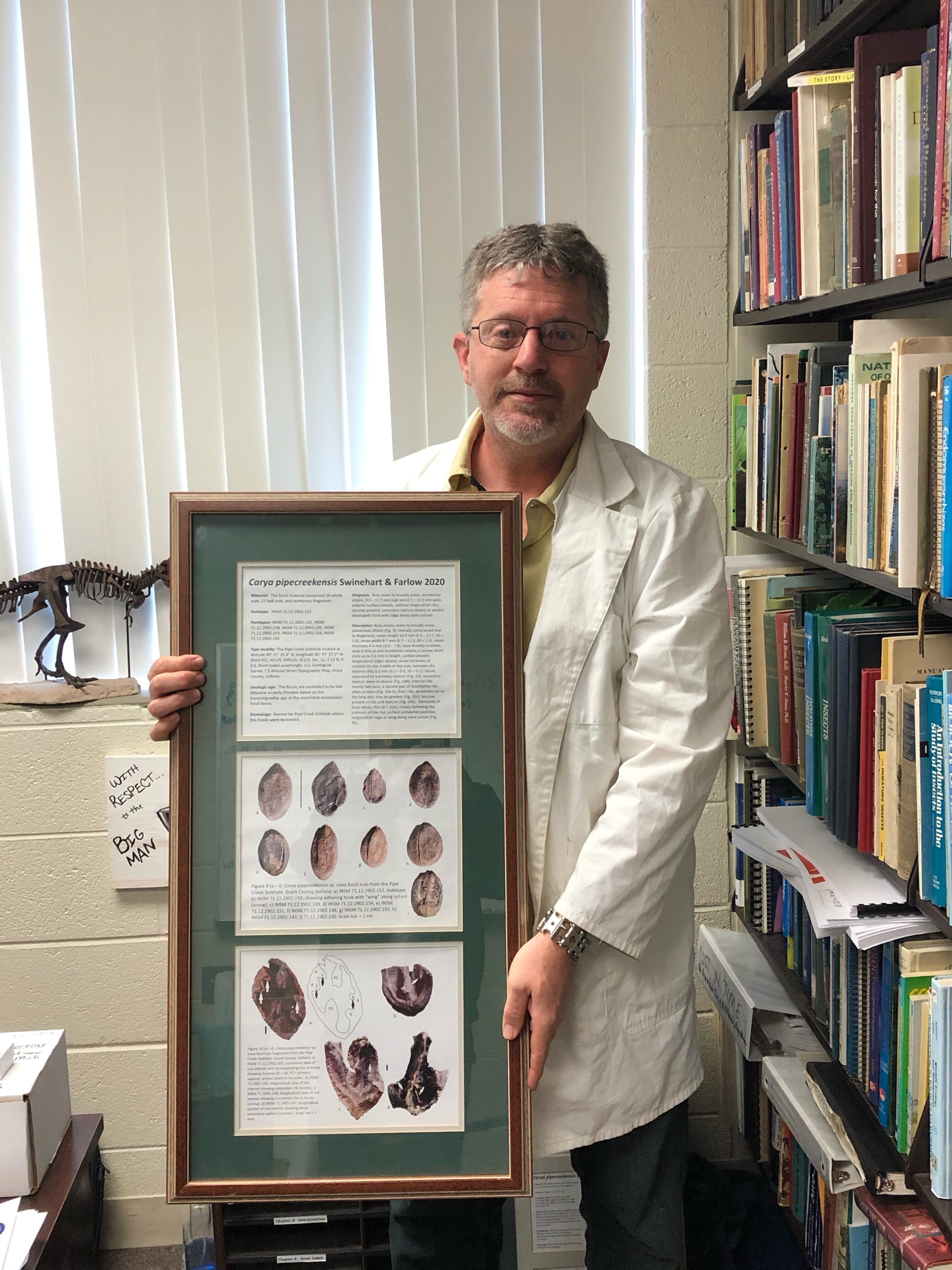

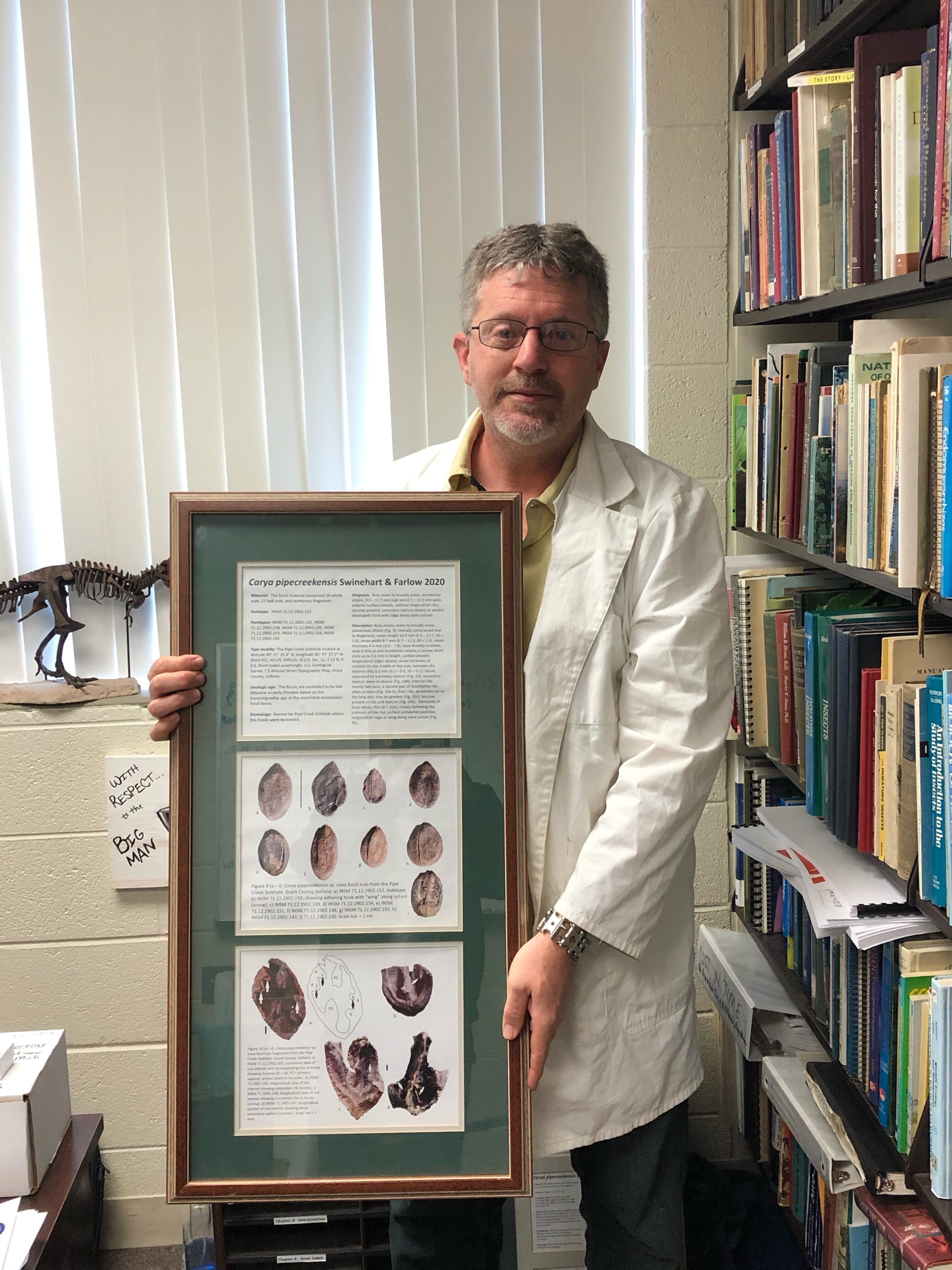

After multiple decades of work and research, Professor of Biology Anthony Swinehart has discovered a new species of hickory tree, the carya pipecreekensis. Along with this discovery comes proof for a significant spatio-temporal range extension of Ginkgophyta (a division of gymnosperms that includes the maidenhair tree and its extinct relatives) in North America.

The discovery came as part of the first ever late Neogene fossil assemblage from the interior of the eastern half of North America, and thus has an incredible impact on the scientific community.

“I don’t have any kids, so there’s my immortality,” Swinehart said. “It’s quite a privilege.”

The site of these discoveries lies in northeastern Indiana, known as the Pipe Creek Sinkhole. It was discovered back in 1996 by a commercial limestone company that was digging in the area.

Upon finding this sinkhole, James Farlow, a colleague of Swinehart, was called in. It didn’t take long for him to realize the significance of the site.

“Right about the time of my birthday, I visited the Pipe Creek Sinkhole.” Farlow said. “I got out of the van, and after only a few steps across the deposit I found a rhinoceros tooth. What a birthday present! I knew then that this site was going to be special.”

Before long, Farlow discovered just how special the Pipe Creek site truly was.

“It is the total diverse assemblage of plants, invertebrates, and large and small vertebrates: a rhino, camels, bear, bone-crushing dog, skunk, badger, lynx, deer, shrew, rodents, snakes, salamanders, turtles, fishes, and huge numbers of frogs.” Farlow said. “A time capsule of creatures that lived in and around a freshwater situation on a dry landscape, roughly 5 million years ago.”

In 1998, Farlow called Swinehart, who he describes as a top expert in plant and invertebrate fossils from freshwater assemblages, asking him to aid in the project.

“He asked me to be the lead author on everything botanical on the site,” Swinehart said. “In addition to all of the big crazy stuff, there were volumes of wood and leaf impressions and seeds.”

The official abstract of the fossil plants and invertebrate assemblage state a large number of fossil finds.

“Examination of macrofossils from the late Neogene Pipe Creek Sinkhole yielded 15 distinct plant taxa, one fungal taxon, and six invertebrate taxa,” the abstract reads. “Fossil nuts of a new species, Carya pipecreekensis Swinehart and Farlow sp. nov., are described.”

Though nearly 22 years passed between his taking on of the project and its completion, Swinehart is grateful for the elongated process.

“Boy am I glad I dragged my feet, because I don’t think that I could have discovered the things that I discovered had I attempted it earlier,” Swinehart said. “I developed as a scientist over that time, and we ended up getting the scanning electron microscope (SEM), which I can’t even begin to describe how that helped in this project.”

With the aid of the SEM, as well as some thesis students, Swinehart was able to discover and describe the Carya pipecreekensis, a type of hickory tree that existed about 5 million years ago. This discovery was made based on a fossilized nut that was found in the sinkhole, the first of its kind.

“All my life, I dreamed of describing my own new species that’s never been described before, and this was probably the best opportunity—maybe the only opportunity—I’ll ever have.”

Surprisingly enough, Swinehart said that the find was indeed a lucky one.

“The whole reason that I was asked to be part of the study was because I was networking. I gave a presentation at the Indiana Academy of Science, and because of that, a door opened.” Swinehart said. “The luck was that Farlow was there, and he had a project that he needed help on.”

In addition to the discovery of the new species, Swinehart’s findings on the spatio-temporal range extension might be a more important breakthrough.

“That actually may be an even more significant find in the paper than the new species in my opinion.” Swinehart said. “What this find suggests is a stronger plant component in North America, and it extends the time we know it was alive here.”

Before this discovery, tree fossils from the same genus were believed to have died out in North America nearly 50 million years ago. Swinehart’s find extended that time by more than 45 million years.

According to Swineheart, the discovery holds immense weight not just for science, but for theology.

“As a person of faith, for those people that say ‘Oh, who cares, it’s some dumb seed of some dumb plant that doesn’t exist anymore,” it reminds me of one of the first commands that God gave to man: give every species a name. Why? Why would you give every species a name? I gave my dog, Trooper, a name,” Swinehart said. “Why did I spend so much time thinking of the perfect name for Tropper? Because he has value to me, and there must be value in every living creature if we’re supposed to think of a name for everyone.”