Since its conception 250 years ago, the Electoral College inhibited democracy. Its original design at the constitutional convention still informs how it operates today: namely, to protect the property of America’s landed class.

Democracy ought to be understood as the foundational assertion that human beings should be able to control their own lives and destiny. Our fate shouldn’t be dictated by a despot, an elected executive, or tyrannical corporations.

Aristotle took democracy seriously and understood its flaws. To account for its shortcomings in government, in “The Politics” book IV, chapter 11, he proposed reducing inequality by ensuring a large, propertied middle class so that less-privileged citizens wouldn’t oppress the wealthy in turn.

The U.S. Constitution’s framers represent a serious departure from what Aristotle had in mind. James Madison in particular saw America’s new government not as a democratic one, but one which, through institutions like an appointed senate and the Electoral College, would be controlled by those who own property.

Thankfully, Madison himself preserved the debates at the constitutional convention with dutiful notes.

“An increase of population will of necessity increase the proportion of those who will labour under all the hardships of life,” Madison wrote. He worried that power would shift into the hands of the working class. “Symptoms of a leveling spirit,” he continued, “as we have understood, have sufficiently appeared in certain quarters to give notice of the future danger.”

Madison, the latest addition to Hillsdale’s Liberty Walk, framed the government to guard against this future danger, which would be brought about by expanding democracy.

“In England, at this day, if elections were open to all classes of people, the property of the landed proprietors would be insecure,” Madison said, according to the notes of Robert Yates. “Our government ought to secure the permanent interests of the country against innovation.”

These conclusions led the framers to construct an appointed senate in order “to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority,” Madison noted, and this attitude informed the construction of the Electoral College.

At the convention, James Wilson proposed a direct election of the nation’s supreme executive. Though the idea appealed to Madison, he recognized that this system would favor the north.

“The right of suffrage was much more diffusive in the Northern than the Southern States,” Madison wrote, “and the latter could have no influence in the election on the score of the Negroes.”

Madison’s worry had little to do with large or small states, but with north and south. Populations between these regions were roughly equal, but if the country decided the president by a popular vote, the sheer number of northerners — who (rightfully) had the franchise — outnumbered that of the southern states. In addition, nearly one-third of the south’s population were enslaved Africans.

Madison’s solution was the Electoral College — to allocate representatives to elect the president based on population, not votes. Coupled with the infamous three-fifths compromise, the Electoral College allowed the south to maintain a presence in presidential elections while avoiding the “innovation” of extending democracy.

The plan worked. For 60 years, until Millard Fillmore sat in the oval office, every president except the Adamses owned slaves. As a result of America’s perverse voting configuration, slavery survived well into the second half of the 19th century, African Americans didn’t secure the right to vote until 1965, and 2020 marks only the 100th year women can vote.

If the framers adopted direct election of the president, states would’ve faced tremendous pressure to “innovate” and extend the franchise since extra votes give individual states more power. Instead, states limited the right to vote to a select few. Southern states could increase their political power by expanding their slave populations, which prolonged slavery and encouraged the slave trade.

The Electoral College apportions voting power equal to the number of representatives and senators a state has in Congress. One common argument for maintaining the Electoral College posits that, without it, candidates will ignore the interests of states with fewer representatives. But this argument makes sense only if we presume that landowners (or land itself), not citizens, should vote. Insofar as there are more individual voters in a state, not more representatives and senators in Congress, that state should gather more attention from candidates.

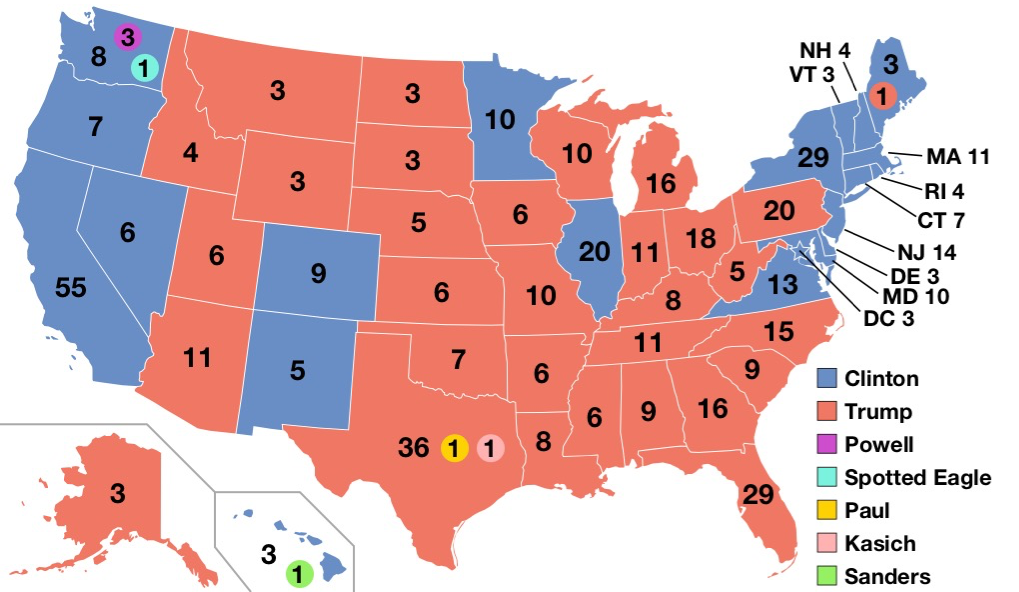

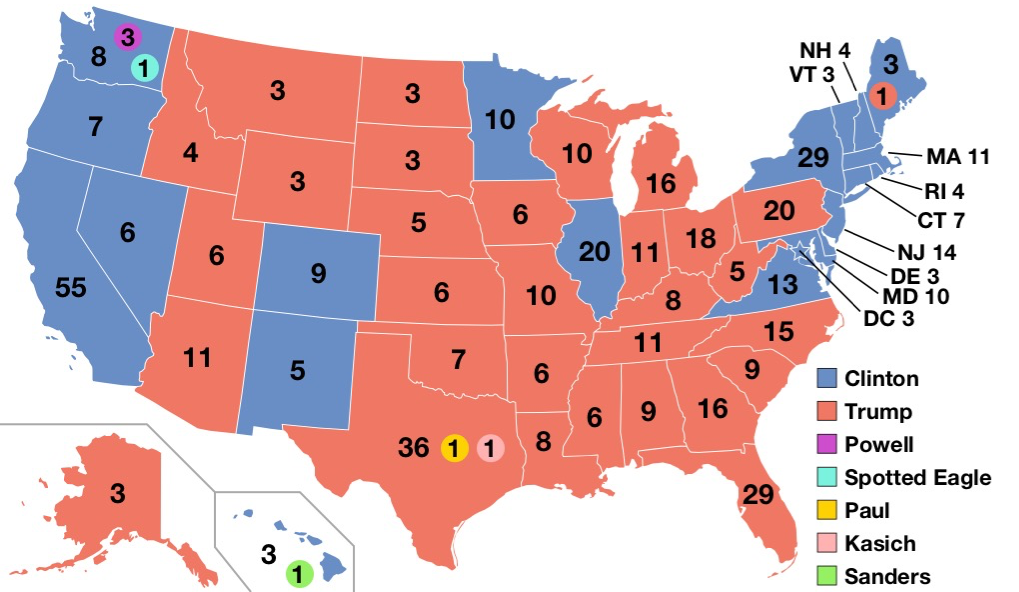

The Electoral College still favors white landowners and disadvantages poor people of color who mostly reside in populous states. Winning smaller states, which generally have much whiter populations than the country in general, offers a significant advantage. In Wyoming, for example, one electoral vote represents about 200,000 people, but in California, one electoral vote represents more than 700,000.

Right now, candidates are rewarded threefold for prioritizing the interests of Wyoming residents rather than those in California. The Electoral College today allows policies which favor the interests of white and wealthy landowners to thrive inordinately: something the framers themselves designed.

As the 2020 election looms large, so do the legacies of our country’s archaic institutions. Only after a reckoning with its founding and the systemic prejudices it produced will America enjoy the fullness of democracy that it flaunts so proudly.

Cal Abbo is a senior studying sociology.