Every family has a handful of recipes that are more than staples: They’re family legend. Gramma’s banana bread, with a vinegar-milk mixture in place of buttermilk. Steve’s chicken chili. George Washington’s pea soup.

The recipes are a weird conglomeration of your parents’ favorites: For me, that’s the stew my dad’s mom always made, a casserole recipe on an old, yellowed magazine page with food spattered inside and outside the plastic slip housing it, and Fannie Farmer’s foolproof griddlecakes.

A used copy of Farmer’s cookbook, originally published in 1896, now runs for a mere $1.99 on Barnes and Noble, and unlike Julia Child and Irma Rombauer, is not much discussed by more modern cooks.

But Farmer was borderline revolutionary in her time. She recorded measurements with scientific precision, and was one of the first cooks to write an instructive recipe book at a time when most housewives either hired a cook or attended extensive cooking school in order to make a good biscuit. Farmer changed that.

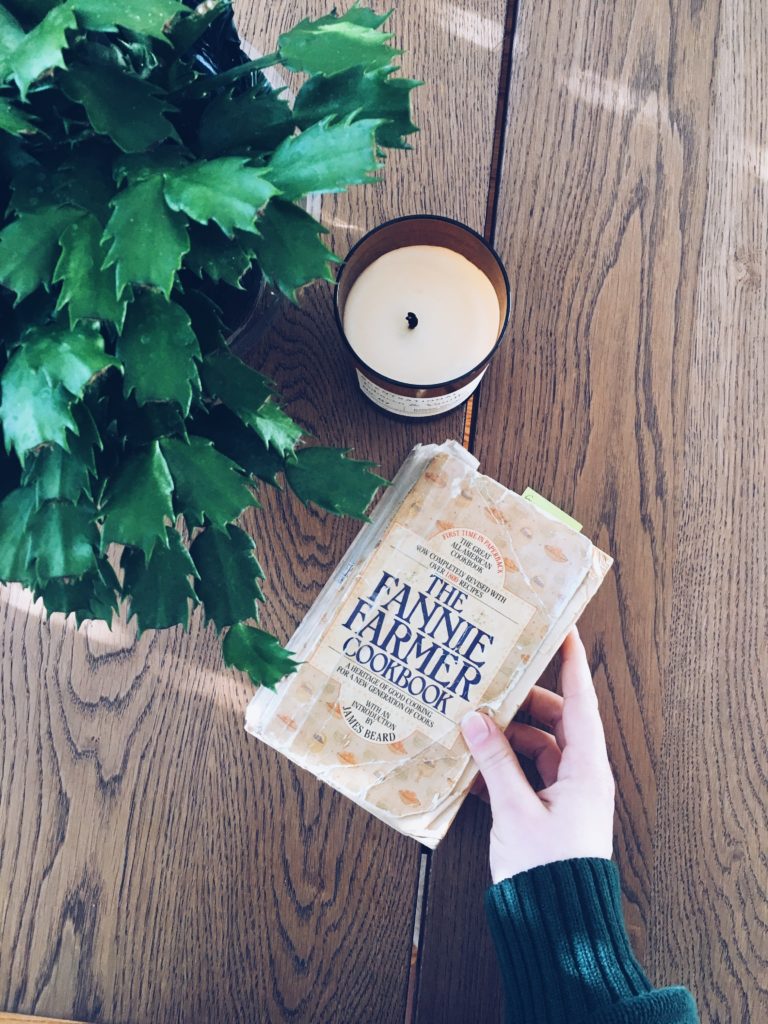

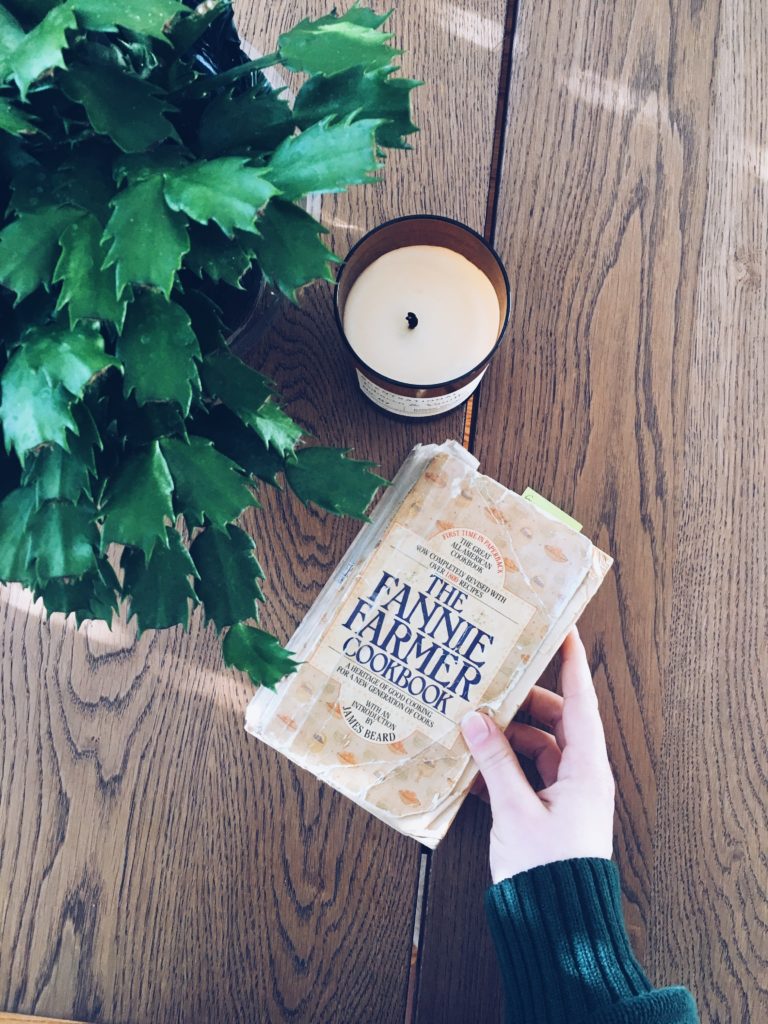

At the front of the cookbook shelf in our kitchen, its title blurred by the layers of tape holding together the spine and a mosaic of greasy fingerprint stains, is a short, fat brown book whose spine falls into two even halves when you pick it up: The Fannie Farmer cookbook. On one side is a page that says “Quick Breads” and on the other is the classic griddlecake recipe — the only pancake recipe I’ve ever used.

Farmer’s personal story was memorialized in Deborah Hopkinson’s 2001 children’s book, “Fannie in the Kitchen,” a personal favorite of mine as a child. The book tells the story of how Farmer, originally hired as a live-in nanny at the Shaw household in Boston, Massachusetts in 1887, ended up helping daughter Marcia Shaw learn to cook through a series of simple rules and precise measurements, while Mrs. Shaw cared for her new baby.

Eventually, Farmer’s skill in the kitchen became renowned among other Boston housewives, to the point where she earned a teaching job at the Boston Cooking School where she attended classes, despite never having finished high school. Before Farmer left the Shaws, Marcia Shaw convinced Farmer to write down her tips, which would eventually become the beloved cookbook that is still in print today, more than 100 years later. (Maybe “Fannie” isn’t in your everyday lexicon, but I bet your mom knows her name.)

Though the children’s book simplifies the real story — Farmer suffered a stroke in high school that left her partially paralyzed and kept her from finishing her formal education — Farmer’s story is still a real miracle of history. Farmer continued to educate herself and others, and even opened her own Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery in 1902. Unlike other cooking schools which instructed hired cooks or teachers, Farmer taught mostly housewives.

“It is my wish that [the book] may not only be looked upon a as a compilation of tried and tested recipes, but that it may awaken an interest through its condensed scientific knowledge which will lead to deeper thought, and broader study of what to eat,” Farmer wrote.

Fannie Farmer’s cookbook taught me that the perfect time to flip a pancake is when it’s puffed and full of bubbles. You’ve got to be patient: You can’t flip it before, and you can’t flip it after. In the sixth grade, I would demonstrate this knowledge in a presentation I titled “How to Make Pancakes,” in which I showcased my Farmer-learned griddlecake expertise to a room of bemused parents and hungry students.

Farmer’s cookbook is more than just good pancake recipes and the three ways to test the freshness of eggs: In many ways, it’s a real embodiment of the American dream. A young woman, with multiple setbacks — physical, social, intellectual — who not only managed to make a living doing what she loved, but also revolutionized food preparation by making it accessible. And she taught other women the skills they would need to do the same, to be self-sufficient.

You don’t have to wait to be formally educated to learn to cook, and even become good at it. You just have to be patient. Fannie Farmer taught me that, too.