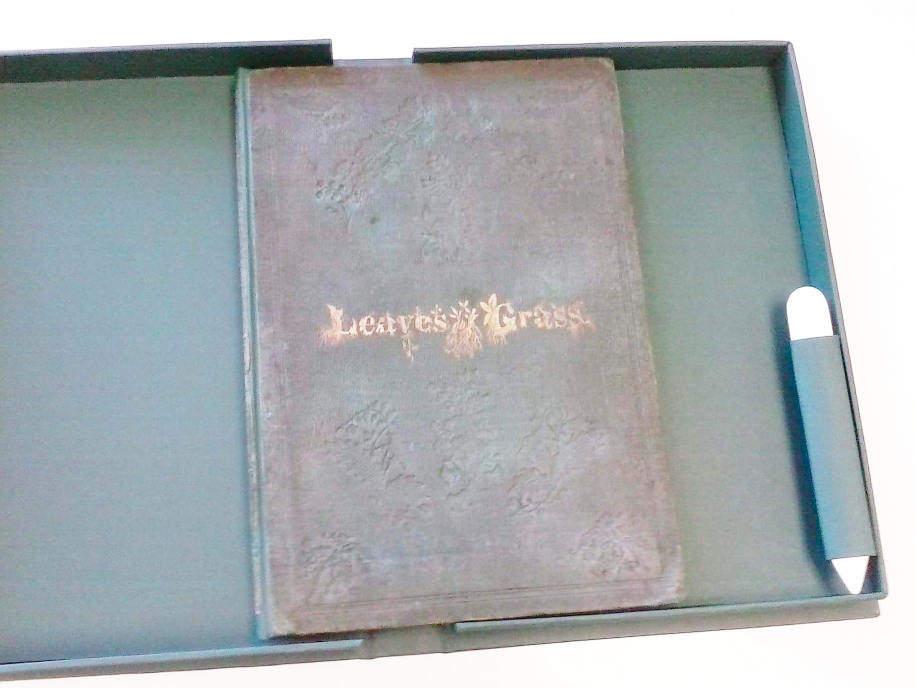

Hillsdale’s first edition, second issue copy of Walt Whitman’s 1855 “Leaves of Grass” has officially returned to the Heritage Room after several months of repairs — a restoration process that has left the book officially appraised at $25,000.

“Our primary interest in restoring the book was in making it something that students could look at,” Public Service Librarian Linda Moore said. Accidentally, however, the restoration process ended up increasing the book’s monetary value, as well. In its original condition, it was only worth $1-2,000.

A woman named Gladys Mathew donated the copy to the college in the 1970s, although Moore said information about who this woman was or why she owned the book has been “lost in the mists of time.” The book had long been in disrepair, and almost nobody asked to see it until Assistant Professor of English Kelly Franklin, a Whitman scholar, started working at the college in 2014 and began using the book to teach students in his Great Books classes.

“It helps bridge the gap of time,” Franklin said. “It enables the students to connect with the book in a deeper and more real way than by just reading a paperback edition.”

“Once he became interested in it, we decided we should try to find someone to restore the book,” Moore said. Although they knew they were running the risk of decreasing the value of the book in the restoration process, the librarians decided it was more important to make sure students could better access the book.

Moore sent the volume to a restorer in November, and it was finished by February. Repairs included replacing the cover’s worn-out boards, adding new tissue inserts between pages, and giving the book a custom clamshell and bone folder for safe handling. The book can again be safely handled by students and used in classes.

When Franklin uses the edition in his classes, he often has students discuss the drawing of Whitman that appears on the inside cover. Because Whitman’s name didn’t actually appear on the first edition of “Leaves of Grass,” this image is the first interaction readers have with the

poet. According to Franklin, examining the picture is a key to understanding the persona the author is attempting to communicate.

“He’s in laborer’s clothes, he’s casual, and his hand is on his hip,” Franklin pointed out. “He wants us to think of him as a common man, someone who wears his hat indoors and out, who doesn’t bow to convention.”

Although Franklin would eventually write his dissertation on “Leaves of Grass,” he disliked Whitman for a long time, finding him egotistical. It wasn’t until he read Ezra Pound’s poem “A Pact” (in which Pound acknowledges that anyone desiring to write poetry in the 20th century must first deal with Whitman), that Franklin decided to give him another chance. In the poem, Pound commends Whitman for readying the world of modern poetry for Pound and others: “It was you that broke the new wood,” he writes, “Now is the time for carving.”

“When I realized that Pound is saying Whitman paved the way for modernism, I was like, ‘Now I’m interested,’” Franklin said. “If I couldn’t have T.S. Eliot without Whitman, I’m interested.”

Professor of English Christopher Busch, an American literature specialist in the English department who also studied Whitman in graduate school, said there is probably “no American poet more important than Whitman.” Whitman, he says, saw himself as consciously answering the call for a bard who would “sing America.”

“Americans of all stripes, of all backgrounds and lives, find their places in his poetry,” he said. “He’s trying to include everything we can think of that is a part of American life into his vision.”

Franklin said Whitman’s “vision of human equality is unparalleled in American letters.” Although in 1855 it was illegal to help an escaped slave, in the pages of “Leaves of Grass” Whitman does exactly this, poetically transgressing a law to make a then-radical statement about freedom.

“He takes equality to an extreme even the abolitionists would have been uncomfortable with,” Franklin said. “He says ‘I am the poet of slaves and of the masters of slaves’ — he insists on being the poet of both. He’s obsessed with union and bringing opposites together and making a poetic voice of shared commonality that the nation really needed.”

Both Franklin and Busch encourage Hillsdale students who may balk at Whitman’s apparent egotism to give him a fair chance. As Franklin pointed out, the first word of “Leaves of Grass” isn’t actually “I” in “Song of Myself.”

“The first word of the book is ‘America,’ in the first line of the prose preface,” he said. “With any great author, we’ve got to understand him on his own terms.”

“I celebrate Whitman because he’s incredibly important,” Busch added. “I would encourage all students to go in with an open mind and try to read and listen to what the writer has to say.”