Writing is, as Joan Didion states in her essay “Why I Write,” “an aggressive, even a hostile act.” In forming words into sentences, stringing them into paragraphs, and lacing those into chapters of books, a writer participates in a sort of coercion. The writer’s goal is to show something to the reader through force of talent. Books, however, should not perpetuate a political and literary culture that continues to cast blame for past crimes.

This year, the National Book Award selection panel decided that violent books with strict political agendas are the most important. Three of the winners — Daniel Borzutzky, Ibram X. Kendi, and Colson Whitehead — have dragged the conversation about race relations further through the desert of American popular literature. These books all speak about cultural identity and the systematic oppression of targeted races as they turn a scornful eye toward those they blame for this injustice.

Borzutzky overtly claims that his poetry is about oppression, not art: “I was thinking about those who cannot survive the brutalities of our rotten economies,” he said about his collection “The Performance of Becoming Human.” Whitehead’s rewriting of the Underground Railroad brings historical oppression to bear on fiction. Kendi’s subtitle to his graphic novel for young adults provides nothing less than “The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America.”

That is not to say these books don’t matter. They are products of the climate of contemporary literature, born in an age obsessed with race and identity, fueled by the institutionalization of these modes of thought in many English departments. They are products of a culture that has sacrificed storytelling for strictly didactic narratives that replace the transcendent for the social trends of the time.

This oft-repeated narrative is neither original nor enlightening; picking up a book subtitled “The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America,” the reader knows what the book will contain. This narrative may be true, but lectures are less effective than original storytelling.

These books follow the tradition of slave narratives that speak about hardship and provide insight into the political and social climate. This does not mean that such books cannot be beautifully written or that they cannot be important in shaping the views of Americans. Books about injustice and struggles with cultural and racial identity have the possibility of shaping the future of our country. But they should not be given awards for literature on their political merit alone. We need a higher standard for our books than retribution for past crimes.

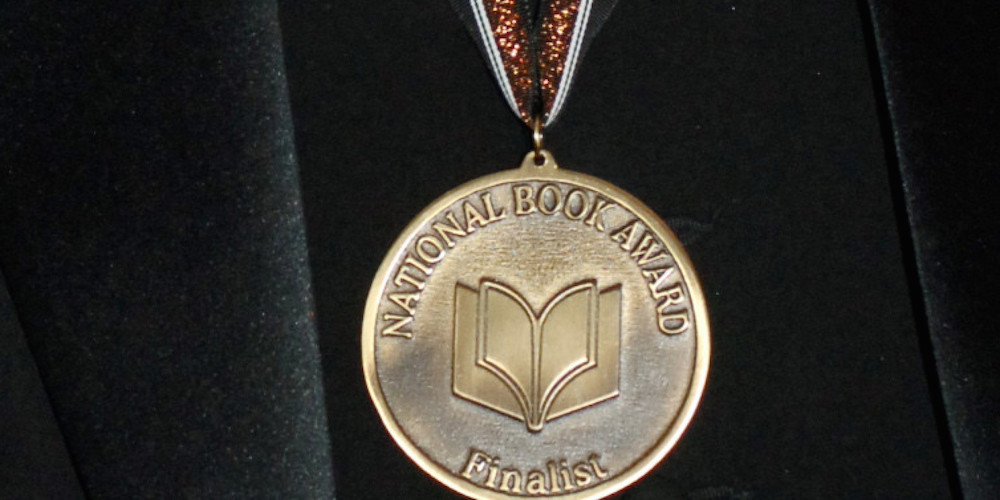

We could turn up our noses and say that the National Book Award doesn’t matter. We have had to do this with the Nobel Prize for Literature, which has given its award to Svetlana Alexievich, a journalist, and Bob Dylan, a songwriter, in the last two years. Neither of these people even claimed to be writing literature. The National Book Award should mean more to us. It matters to the nation. It sets the pulse.

The Selection Panel decided that excellence in writing equates to political forcefulness. But the best literature does not follow an agenda; it forms a world through the expression of a truth that does not deny, but instead transforms culture.

The mission of the National Book Award is “to celebrate the best of American literature, to expand its audience, and to enhance the cultural value of good writing in America.”

The Selection Panel did not accomplish its goal. It bowed to culture and media, enshrining confessional books in the canon of American literature. These are books that, because of their award, will be purchased and read by hundreds of thousands of people. The Panel used their position as the arbiters of the American literary pulse to dilute culture, instead of holding the beauty of the written word up to the nation.