Nicholson Baker’s mind captures the “fine suddenness” of every moment. His work fixates on the minutiae of the everyday experience while largely ignoring the notion of a plot. His dense, accurate prose tightens the reader’s grip on reality. Two of his more recent projects, however, develop a compelling and sophisticated narrative. His two most recent novels, “The Anthologist” (2009) and “Traveling Sprinkler” (2013) focus on a single character, Paul Chowder: a minor poet whose neuroticism, tenderness, and penchant for hyper-accurate description come straight from Baker himself.

“The Anthologist” opens as Chowder’s live-in girlfriend, Roz, leaves him because of his stasis and inconsistency in his own life and in their shared life together. Having compiled an anthology of poems centered on rhyme, he cannot bring himself to write the introduction. The book operates as Chowder’s attempt to explain the importance of rhyme while simultaneously providing a look into the mind of a heartsick man.

The second novel, “Traveling Sprinkler,” opens after the publication of Chowder’s anthology as he develops the inclination to become a songwriter, focused on writing a catchy dance hit. The stunning insight into the history and theory of poetry provides sharp contrast to Chowder’s seemingly frivolous goal. Yet Baker combines these two elements to explore the relationship between song lyrics and poetic verse, as Chowder struggles to write a great love song for Roz.

The two novels should be thought of a sequence — a long rumination on the possibility of poetry and the role of the artist. Baker employs a first person conversational narration style that mirrors the unconventional method he used in writing both novels.

In his “Art of Fiction” interview with the Paris Review, Baker said he wrote the book by “speak typing” while dressed as Paul Chowder, giving an extremely long dramatic monologue full of digressions. This writing method gives the novels a raw, idiosyncratic quality while engaging directly with the reader, as if in conversation. The strange and amicable voice is a direct result of Baker’s technique, a combination of theatrics and stream-of-consciousness.

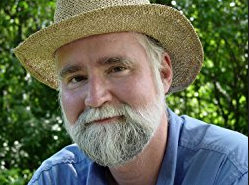

In the “Art of Fiction” interview, Baker said, “When I started ’The Anthologist’ in 2003, I dictated notes into a digital recorder and transcribed some of them and set that aside. And then in 2007, I did a lot of videotaping of myself talking in the character of Paul Chowder. I set up a camera and grew quite a huge beard and tried to be a poet. I had this old fisherman’s hat that I wore. I shot about 40 hours of me in various places, outside, down in the creek.”

Paul Chowder becomes a true alter-ego for Baker, whose natural wit and charm permeate the narrative. Through this alter ego we see Baker’s mind most accurately. His mind creates absurd connections and obsesses over the unrecognized particularities of life, while expelling empathy and love at every turn.

Chowder loves fully and realistically. He fixates on Roz’s dating life during their romantic hiatus while looking to impress her whenever the opportunity arises. Readers are likely to find Chowder intensely relatable despite his oddities and fixations. He obsessively cleans his workspace, smokes cigars to emulate other great poets, worries about drone warfare, and fixates on writing poems about flying spoons. At the end of “Traveling Sprinkler,” he comforts Roz after she undergoes a hysterectomy. This moment is a profound realization that the couple missed their chance to have children.

In Chowder, Baker constructs a neurotic everyman who is true to life. In his eccentricities and challenges, Chowder shows us more about ourselves and how overcome our anxieties in order to love fully and deeply.

The novels are also a grand celebration of poetry from a mildly intellectual minor poet. From his position, Chowder can attest to his love of poetry, as well as his struggles with it. A primary fixation “The Anthologist” is Chowder’s claim that iambic pentameter actually mirrors waltz timing with a three beat line, instead of the common misconception that a line of iambic pentameter (as in Shakespeare) contains five beats. His argument hinges on the idea that there is a breath at the end of each line of poetry. Correct or not, these digressions show the creative mind at work while also helping to define Paul Chowder as a thoughtful, affable character.

I once asked a friend of mine, a poet from Maryland, what he thought was the common thread in his poetry. He looked at me as if I had asked what year it was. He replied simply, “Well, every poem is a love poem, of course. The reason you write at all, is all out of love.”

This is what Baker proves with these two novels as he distills beauty from the quotidian, offering the sympathetic voice of a bumbling protagonist with too much in his heart. Baker uses Paul Chowder to show us part of himself, and in so doing, shows the possibility that we too can be driven to love so ardently.