According to a Time magazine list of the top 100 young adult novels, “We’re living in a golden age of young-adult literature, when books ostensibly written for teens are equally adored by readers of every generation.”

The widespread popularity of young adult fiction shows that readers of all ages appreciate the message of hope that mark the enduring works in the genre: Battles can be won. Love can be found. Dragons can be slain.

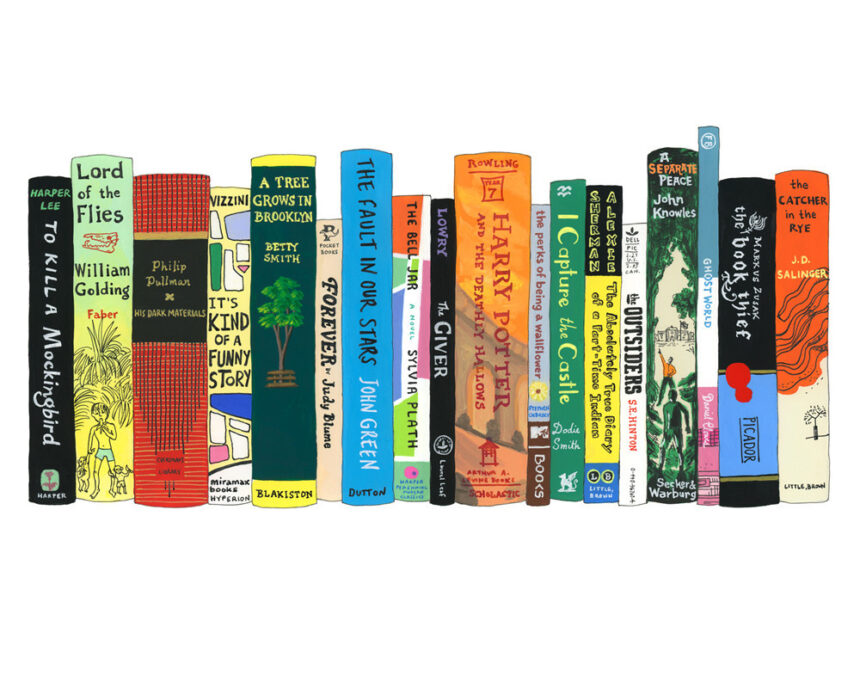

The reading public has not always been as stratified as it is today. The term “young adult literature” appeared in the late 1960s when writers such as S.E. Hinton in “The Outsiders” began to focus expressly on the struggles of “adolescents,” another newly-minted term for people lost in the abyss between childhood and adulthood. Passionate stories of identity, belonging, and young love eclipsed nostalgic, out-of-touch stories written — condescendingly — “for” children.

But even before this distinction separated children’s and young adult literature, generations of adults have taken refuge in young people’s stories. Two masters of the genre, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, returned to fairy tales throughout their lives.

C.S. Lewis, whose “Chronicles of Narnia” could be considered the quintessential fantasy story for all ages, said literature should not be marketed to specific age groups. Lewis said that children’s literature improves with age.

Tolkien took this further. “Insofar as [fairy stories] have been so banished, they have been ruined,” he said. For Tolkien, a good story is valuable at any age.

Daniel Coupland, professor of education, said students in his children’s literature class gain a deeper understanding of stories from their childhoods, including Aesop’s “Fables,” “The Wind in the Willows,” and “Pinocchio.”

But depth of understanding is not the only attraction of young people’s literature. Meghan Gurdon, children’s book reviewer for the Wall Street Journal, said young adult books like Ruta Sepetys’s “Between Shades of Gray” offer a challenge to readers.

“Teenagers have a natural instinct for stories of grueling challenge: it’s a time of life when we’re venturing into the world, and it makes us ask: do I have what it takes to survive?” Gurdon said. “Could I make it through an avalanche or a zombie apocalypse, or the hunger games — or even just a high school filled with mean girls? Books allow us to live vicariously, to try on personae, to seem to be experiencing these brutal tests, without risking our actual lives.”

But in a reading culture inundated with every possible variation on the vampire romance and the “awkward girl gets popular boy” story, all young adult fiction is clearly not created equal.

“A lot of young adult literature seems to be merely therapeutic. We tell kids, ‘It’s okay,’” Coupland said. “But what about rising above our problems?”

Though teachers and parents often hail the young adult fiction craze for bringing children back to the library, some stories give readers what they want, not what they need. Writers imagine — often rightly — that teens want to escape the anxieties of adolescence through glorified daydreams: What if that boy asked me out? What if zombies took over the world, and I had to fight them? What if a zombie and I fell in love? What then?

But for a young adult fiction novel to resonate beyond the hallways of high school, it must offer more than a mental refuge. It must take readers on a journey that teaches them how to live, transporting the reader out of his weary life and into an adventure in which characters grow, learn, and conquer their struggles.

Young adult literature draws its strength from adolescents’ passionate search for identity in their teenage years. Done poorly, this devolves into an indulgence of teens’ fantasies. Done well, young adult literature can be a powerful expression of discovery and hope.

“Fairy tales do not tell children the dragons exist,” G.K. Chesterton said. “Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children the dragons can be killed.”

The rising popularity of young adult fiction shows that a story’s value lies not in its label, but in its promise that dragons — no matter their shape, size, or target audience — can be slain.