Maurice Manning’s poetry in his 2010 collection “The Common Man” is an invitation to converse with the unique voices of his rustic Kentucky home. Manning uses each poem as an opportunity to narrate a single tale. But beyond merely relating events, his narrators sing of themselves, their concrete personalities and manners, and their relationships to their neighbors, the natural world, and the Divine.

Maurice Manning’s poetry in his 2010 collection “The Common Man” is an invitation to converse with the unique voices of his rustic Kentucky home. Manning uses each poem as an opportunity to narrate a single tale. But beyond merely relating events, his narrators sing of themselves, their concrete personalities and manners, and their relationships to their neighbors, the natural world, and the Divine.

Reading these poems can feel like a face-to-face encounter with a fully-realized persona that tugs on your ear or wafts across a fire. The collection’s combination of conspiratorial, illicit, or legendarily scandalous activities with philosophizing creates a marvelous friction. For instance, the first poem begins with a swig of moonshine that provokes reflection on family, place, and storytelling. In poems like “That Durned Ole Via Negativa,” metaphysical and Kentuckian worlds collide as an audibly uneducated, ungrammatical speaker meditates on the transience of a painful world: “You can’t say naw / without the trickle of a smile. / . . . / Down in / that gloomy sadness always is / a hope. . . . My, / but we’re in a lonesome country now. / I wonder if we ever leave it? / We could say yeah, but wouldn’t we / be wiser if we stuck it out / with naw.”

The voices’ unpracticed air lends them a real quality. The narrators hesitate, reconsider, digress, and distract themselves, all the while revealing the significance each moment they relate has represented in their own stories. As Manning’s opening poem concludes, “This was the first time I heard the story / I was born to tell. The first time I knew / That I was in the story too.”

The idioms, myths, and settings of Manning’s native countryside furnish each poem with a purposeful definition that makes the tales accessible

and immediate, giving access to the personal and communal history of Manning’s Kentucky childhood. These are poems best read out loud, and slowly, in a group. Solitary reading can make the narratives feel repetitive and forgettable, however evocative on their own.

Many of Manning’s poems are about the natural world and about God, betraying the poet’s confessed inspiration from Gerard Manley Hopkins. Poems such as “Prayer to God my God in a Time of Desolation” are addressed through the narrator’s complicated relationship with a remote God, who bears questions and accusations drawn from the struggle of the prayer-giver to understand himself as he was created. Others are honest and comic tales of country life retold by their more bookish, but sympathetic, hearer, whose literary titles might sometimes contrast with his subject matter — for example, “The Old Clodhopper’s Aubade” or “Ars Poetica Shaggy and Brown.”

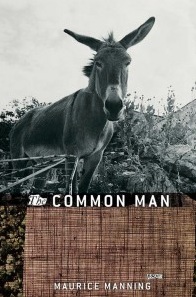

More of Manning’s personality is revealed in meditations on animals, which take special significance for anxious narrators more at home among farmstock than with their broken or fragile relations with neighbors and family.

The unpretentious verse of “The Common Man” is no excuse for Manning to avoid reflection on perennial poetic subjects, and the accessibility of his rhythmic couplets means this collection is easy to recommend to lovers of poetry.