The top song on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1965 was a cover by the British group Herman’s Hermits. It had only one verse, repeated ad nauseum:

“I’m Henery the Eighth, I am.

Henery the Eighth I am, I am!

/ I got married to the widow next door;

she’s been married seven times before,

/ And every one was an Henery,

it wouldn’t be a Willie or a Sam.

/ I’m her eighth old man, I’m Henery,

Henery the Eighth I am!”

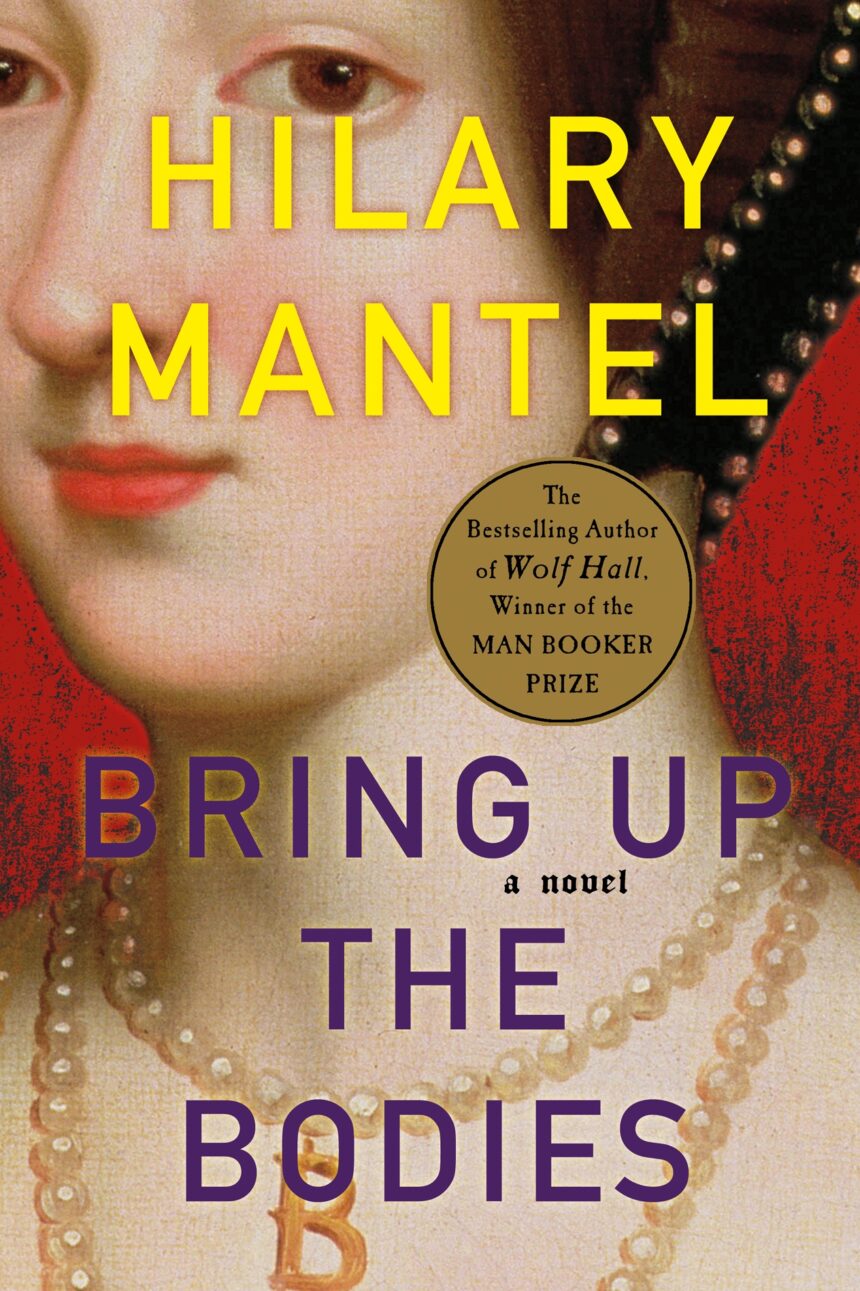

It’s a wink at the gruesome fun fact everyone knows about English history — the king who beheaded and divorced his way through six wives in the quest for marital happiness and a son to rule after him. But what if Henry VIII was really a soulful lover, and Anne Boleyn a conniving survivalist? If St. Thomas More died as a stubborn hypocrite, while Thomas Cromwell acted like a decent, albeit opportunistic, statesman. This is the setup for Hilary Mantel’s tightly written novel “Bring Up the Bodies,” a sequel to her lauded 2009 effort “Wolf Hall.”

The year is 1535, and Henry is growing restless with Anne, known to most of Europe as “the concubine.” Catherine of Aragon sits dying in reclusion, cast aside because she had failed to provide the king a son. The Holy Roman Emperor, Catherine’s nephew, watches for a chance to punish Henry. The king of France hovers between alliances while Henry hovers between Anne Boleyn and the pale Jane Seymour. Second verse, same as the first. In the middle sits secretary Thomas Cromwell, a man of low birth whose intelligence, savvy, and bulldog tenacity have made Henry powerful and Thomas indispensable — at least for the time being. Many of the nobility would like Cromwell dead, chief among them the Boleyn family. In this tense situation, Mantel weaves politics, friendship, loyalty, love, desire and revenge into a surprisingly straightforward story arc with an unusual narrative technique, a third person stream of consciousness that still employs the typical third person focus on dialogue and action.

By always referring to Cromwell simply as “he,” Mantel draws the reader close to Thomas’ thoughts and perspective without resorting to the vogue but annoying first person present tense. Cromwell emerges as complex, thoughtful, and humorous — a good man who does bad things for his king. The book’s title refers to the bodies of the men (including Anne’s own brother) beheaded for sleeping with the queen, who met the same fate herself a few days later.

Mantel does not ask the readers to believe that Henry acted justly. He did, after all, hire an executioner before, not after, Anne’s trial. Cromwell believes that Anne and her “lovers” were perhaps not guilty of adultery, but they were certainly guilty of evil and so deserved to serve the king with their deaths. By giving the king and his secretary souls — and portraying the Boleyn’s as sly and promiscuous — Mantel essentially agrees with Cromwell, which makes the novel such a compelling read.

Mantel’s prose style is elevated but accessible. She has done her homework, and claims in the afterword to be giving a careful historical reading of the events. That reading somewhat cuts across both recent scholarship and the popular concept of the lascivious king obsessed with sex and progeny. Alison Weir’s 2010 “The Lady in the Tower” gives a defense of Anne Boleyn as the innocent victim. It’s hard to find an image from the popular Showtime series “The Tudors” that isn’t of someone fornicating.

Mantel overcomes that temptation. She keeps the bedroom door discreetly closed and leaves us whispering outside with the courtiers, and thus achieves a refreshing novel about people using sex and power as weapons, rather than about sex and power themselves. The occasional grammatical error (use of “who” in place of “whom”) and Mantel’s overuse of vulgarity distract from her otherwise elegant book. The damage, however, is slight, and “Bring Up the Bodies” succeeds both as highbrow entertainment and in sympathetically resurrecting the characters of Tudor history.

Henry, of course, didn’t have the best luck with Anne Boleyn’s replacement, Jane Seymour, who died just a year after becoming queen. The homely Anne of Cleeves lasted about six months. The beautiful Kathryn Howard lost her head for sharing her body, a la Anne Boleyn. Only the twice-widowed Katherine Parr outlasted Henry, and married her fourth old man, Thomas Seymour, just months after the king’s death. Mantel’s upcoming novel “The Mirror and the Light,” due in May, will follow the king and his secretary through these years, up to the fall from grace and final destruction of Cromwell.

ptimmis@hillsdale.edu